February 28, 2019

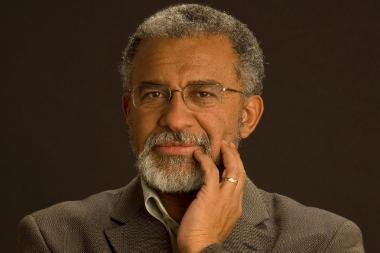

Dr. Johann Buis is an Associate Professor of Music at Wheaton College. He has been published widely in journals such as College Music Symposium, Ethnomusicology, and Early Music America. As Black History Month draws to a close, Buis wrote this Wheaton Experts post, which reflects on the qualities of Black music in America and its enduring impact.

For centuries, Africans and their descendants have made a huge contribution to American music. In fact, when most people think about American music, what many actually call to mind is Black music—jazz, blues, spirituals, Black gospel and hip hop. What people don’t often consider is why these genres arose in America. Here’s a quick dive into the sociological context for the rise of the nation’s Black music—and why it’s become a part of the fabric of the country.

For centuries, Africans and their descendants have made a huge contribution to American music. In fact, when most people think about American music, what many actually call to mind is Black music—jazz, blues, spirituals, Black gospel and hip hop. What people don’t often consider is why these genres arose in America. Here’s a quick dive into the sociological context for the rise of the nation’s Black music—and why it’s become a part of the fabric of the country.

The trope of reconfiguration is present as black agency encounters Western European music. For instance, spirituals are the reconfiguration of a gospel of love, despite the brutality of the enslaved experience at the hands of them who brought this message of good news. Jazz is a reconfiguration of black rhythmic and harmonic vitality that black musicians embraced in conversation with European-derived musical expressions. Blues, according to Austrian ethnomusicologist Gerhard Kubik, is a reconfiguration of the West Sudanic heptatonic scale patterns that Westerners erroneously refer to as non-diatonic “blue notes.” Black gospel music, a genre that emerged during the 20th century, reconfigured the syncopated expressions of the dance hall with the sacred content and workaday imagery in praise of Jesus and the new life of the gospel, the good news.

Through its improvisational impulse, repetitive complexity, and rhythmic pulsation, Black music functions in rhetorical constructions often unfamiliar in Western music. African-American music (for discussion purposes, the term is used here interchangeably with Black music) responds to the individual and societal manifestations of love, pain, empathy, sadness, injustice, and a plethora of vices and virtues of the human condition. The improvisational impulse of Black music gives expression, at times, to call-and-response figurations between soloist and chorus. Additionally, the repetitive complexity within a seemingly uncomplicated circularity leads to new revelations. Rhythmic pulsation nearly always drives such constant restatements of musical patterns. We discover that the circularity of repetition is not simply non-linearity; rather, it is the presentation of a gestalt which allows us, through repetition, to become aware of the threads that make up the total multi-layered fabric of vamps, riffs and similar patterns.

Likewise, the textual repetition in Black music is not simply textual sameness for its own sake. Instead, it allows the listener-participant to enter a degree of meditative practice that is regulated by the leader to the optimal communal “temperature”—the climactic moment of heightened expression—and then released to end the experience. These performative expressions are laden with emotional valence. The intensification of the emotional energy in Black musical performance jettisons the Western notion of timbral purity, in favor of timbral distortions. These timbral distortions include falsetto, groans, grunts, and similar devices that intensify the emotional expression of the text or the melody line. All these devices of improvisation, repetition, emotional (agogic) intensification, as part of the overall gestalt in Black musical performance, are manifestations of an African aesthetic framework.

Today, Black music’s improvisation, repetition and emotional intensification are at the heart of American popular music and Contemporary Christian Music (CCM). That’s why for years Black music has served the popular musical lingua franca so well, both in the dance hall and the church.

The Conservatory provides its students with an intellectual understanding of the various aspects of musical practice, encourages them to reach the highest possible level of artistic achievement, and places this education in a Christian context that describes music as an act of worship and service. Discover more information about the Conservatory.