February 14, 2018

McKenna Fitzharris '18 is an elementary education major with an endorsement in teaching English as a second language. She's from Fort Wayne, Indiana.

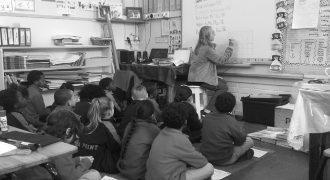

Last semester, I completed my student teaching in Cape Town, South Africa, at an international school. I was placed in a first-grade classroom with 18 students from all over the world—I had students from France, the Netherlands, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Zimbabwe, Angola, Mozambique, Turkey, and Iran. My mentor was an extremely competent cooperating teacher who had been teaching for 37 years and previously worked with nine other student teachers. She was extremely warm and friendly towards me—she offered to do my laundry multiple times, had me over to her house for a steak dinner, and frequently invited me out to their family dinners. She was a phenomenal cook and would bring in portions of food for me to try at least two times a week, including everything from homemade corned beef, lemon meringue pie, and fresh koeksisters, a South African dessert that is a spiced donut hole rolled in coconut. My teacher would often share bits of her four children’s lives with me, told me her retirement plans, and related some of her own experiences of growing up in Cape Town to me.

Last semester, I completed my student teaching in Cape Town, South Africa, at an international school. I was placed in a first-grade classroom with 18 students from all over the world—I had students from France, the Netherlands, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Zimbabwe, Angola, Mozambique, Turkey, and Iran. My mentor was an extremely competent cooperating teacher who had been teaching for 37 years and previously worked with nine other student teachers. She was extremely warm and friendly towards me—she offered to do my laundry multiple times, had me over to her house for a steak dinner, and frequently invited me out to their family dinners. She was a phenomenal cook and would bring in portions of food for me to try at least two times a week, including everything from homemade corned beef, lemon meringue pie, and fresh koeksisters, a South African dessert that is a spiced donut hole rolled in coconut. My teacher would often share bits of her four children’s lives with me, told me her retirement plans, and related some of her own experiences of growing up in Cape Town to me.

All this to say, I thought I knew my cooperating teacher very well—I had shared a meal in her home, eaten her food, helped with her daughter’s wedding planning, and could probably name every street she had lived on in Cape Town. However, about a month after arriving in Cape Town, I went to The District Six Museum, and what I thought I knew about my teacher was completely shattered.

The District Six Museum is one of the many museums dedicated to sharing the story of apartheid in South Africa. It focuses on Housing District Six, a housing district that was declared a “whites only” area in 1966 under the Group Areas Act. As a result of the Group Areas Act, by 1982, 60,000 people had been forced out of their homes in District Six and were relocated to the townships, which are slum areas outside the city of Cape Town.

The most poignant room in the museum for me had 12 giant framed photographs on display. Each photograph—all stark black and white photos of a District Six residents whose last names were the names of months—was captioned with a month of the year in huge letters. A short testimony about their exile from District Six was also included.

My cooperating teacher’s last name was a month of the year, so I was immediately intrigued by the room.

At the entrance, there is a small plaque with a description of the purpose of the room. The plaque states that the government changed many District Six residents' last names to the month they were forced out of the district.

I was shocked and heartbroken, immediately thinking of my teacher. I recalled stories she had told me of her parents living in the city, next door to their best friends, and then “having to move” outside the city where they suffered immensely in so many ways.

While my teacher had never explicitly shared with me that her parents were residents of District Six and were forced to give up their home to a white family, all the dots connected as I was standing in front of the portrait with her last name at the top, silently crying.

This proved that even though I had spent time in my teacher’s home, and listened to countless stories about her children, I was still not fully aware of the suffering she and her family endured as a result of apartheid in South Africa. This encounter also reinforced the disheartening and deeply frustrating reality I was becoming more and more aware of—the continuation of the apartheid. While legally the apartheid system was struck down in 1994, its traces still run rampant in the country, evident in the education system, job market, housing segregation, and corruption.

From that day on, every time I said my teacher’s last name, I was reminded of the fact that you can never really fully know someone, and of the many citizens of South Africa who are living every day with potent reminders of apartheid.