Featured Courses

Many Courses from Which to Choose

Revelation, Letters, and Apostolic Fathers

Greek 346 (4 Credits)

“Fourscore and six years have I been His servant, and He hath done me no wrong. How then can I blaspheme my King who saved me?” ~ Polycarp

“But if thou hast not living water, then baptize in other water; and if thou art not able in cold, then in warm. But if thou hast neither, then pour water on the head thrice in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit.” ~ Didache

Read (and informally discuss) the entire Greek texts of Revelation, Hebrews, Jude, Didache, and the Martyrdom of Polycarp, along with selections from Epictetus and Josephus! As Koiné texts, these are a natural next-step after 201 and an effective way to put down roots in the language. They are also works on which life is reliably built.

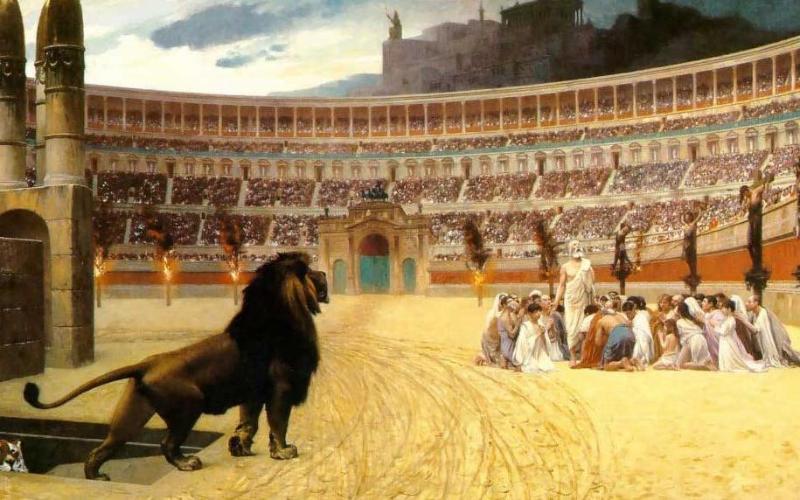

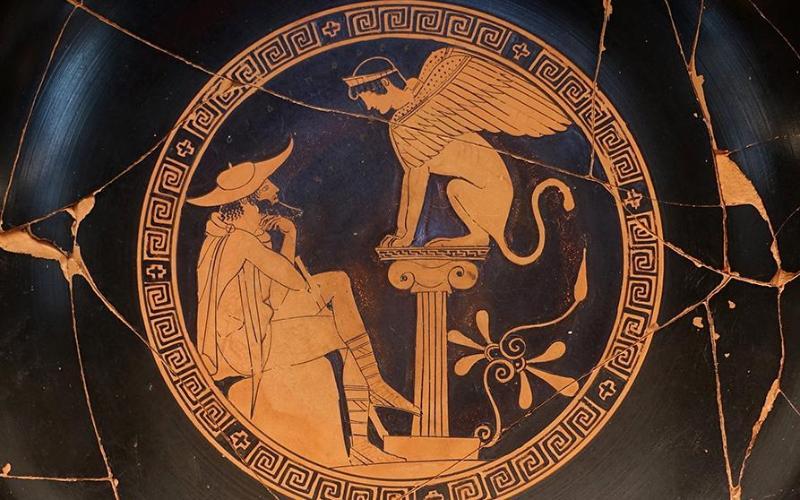

Oedipus the King - Athenian Tragedy

Greek 331 (4 Credits)

Can you overcome destiny? Are you responsible and blameworthy for actions you were destined to commit? What if you committed the worst atrocity you could imagine in complete ignorance. How would you respond? Are there certain horrifying truths of the world better left unknown, or must even the darkest secrets be revealed? Oedipus the King is one of the most profound meditations on these questions ever written. It influenced thinkers and artists through the ages, from Aristotle, Hegel, and Kierkegaard to (infamously) Freud and his “Oedipus complex. ”Come and read this tragedy in its original, glorious Greek this fall. The course will introduce you to the dialect of Athenian drama as well as its history and conventions. The pace will be slow and careful, allowing ample time for contemplation of Sophocles’ pellucid Greek poetry and the philosophical and literary giants that have responded to it.

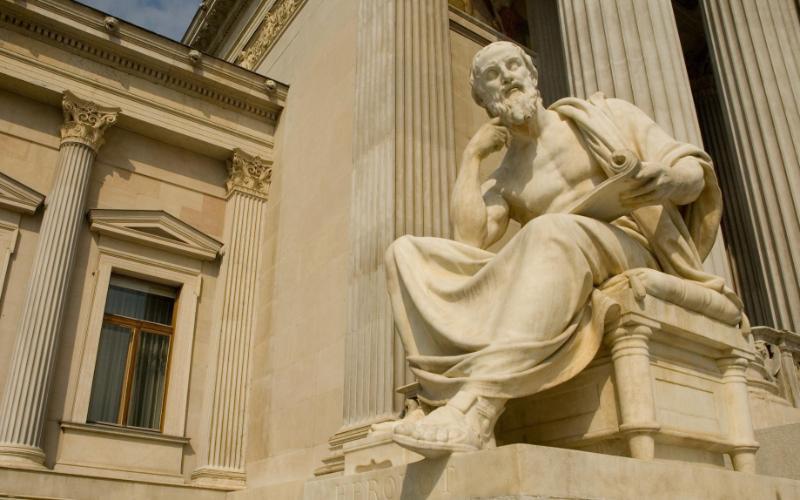

Herodotus

Greek 338 (4 Credits)

In 480 BC, 300 elite Spartan warriors held off an entire vast Persian army, supposedly 300,000 strong for two days. This event, the battle of Thermopylae, is the most storied and glorious defeat in western military history. In this Greek 338, we will read the breathtaking account of the battle by the first historian who ever wrote: Herodotus. Herodotus, a native of Halicarnassus, a Greek city in Ionia (modern day coast of Turkey), wrote the first work of history in the West (in the mid 5thcent. BC). He, in fact, gave the word “history” (historiē) the meaning it has today. For that reason, he is known as the “Father of History.” The central concern of his great work, called “The Histories” (literally, “investigations”) is the Persian Wars—the series of massive battles in which Greece united to defeat a foreign, despotic power and preserve the freedom of the West (or so Herodotus tells it). That is the triumphal story Herodotus wants to tell; the reality is a bit more complicated, as we shall see... Along the way, we hear reflections on fate, ethnicity, language, religion, gender, culture... Herodotus is also the father of anthropology and a sophisticated (if biased) interpreter of the myriad people he encountered or heard of in his known world. In this course, we will become intimately familiar with Herodotus and his work, through the close-reading of his Greek text and through reading in translation his whole body of work.

Ovid’s Metamorphoses

Latin 333 (4 Credits)

Fulfills Literary Explorations (LE) tag

Why study Ovid? Why the Metamorphoses? Ovid is perhaps the single most influential poet in the Western tradition. His Metamorphoses created a “bible” (so to speak) of Greco-Roman mythology. This epic poem encompassed the creation of the world, the inauguration of the Roman empire under Augustus (imagined in Ovid’s day as if it could last forever...), and everything in between. We have the wars between the gods, the creation of human beings, the best-known version of a Greco-Roman flood story, Orpheus—the great mythic poet—descends into the underworld and charms the gods through his songs to give him back Eurydice, only to lose her again... Icarus flies too high; Narcissus loses himself in his reflection; Arachne beats Minerva (=Athena) in a weaving contest; Phaethon takes the keys to his father’s chariot and crashes it; plus much, much more....Even quite strange things :Hermaphroditus and Tiresias undergo sex changes; Pythagoras delivers a detailed sermon on reincarnation...We will read the poem in its entirety in English, plus some representative sections in Latin. A particular focus will be passages that have Biblical analogies. At every turn, this poem speaks to something about the Christian story: about the man who, not unlike Orpheus, harrowed Hell and saved those he loved; the virgin, similar to Danae, the mother of Hercules, who conceived a son by God who would become humanity’s champion against the evil of the world...All this we will discover in the beauty of Ovid’s Latin verse.

Readings in Paul and the Apostolic Fathers

Greek 346 (4 Credits)

“For Christians are not distinguished from the rest of humankind either in locality or in speech or in customs. But while they dwell in cities of Greeks and barbarians as the lot of each is cast, and follow the native customs in dress and food and the other arrangements of life, yet the constitution of their own citizenship, which they set forth, is marvelous, and confessedly contradicts expectation.” ~ Epistle to Diognetus

Paul’s letters to the Ephesians, Galatians, and Titus, his first to the Thessalonians and the Corinthians, Ignatius' letters to the Ephesians, Romans, Polycarp, and Polycarp’s letter to the Philippians. Read together the Greek of all of those in their entirety plus a few chapters from the Epistle to Diognetus! As Koiné texts, these are a natural next-step after 201 and a great way to put down roots in the language. As for contents, few exercises could promise a better return on time and treasure.

Homer: The Iliad

Greek 332 (4 Credits)

This course focuses on Iliad, especially books 1, 3, and 6. From its very first word—mēnis—the Iliad confronts its readers with the problem of the Greek hero. Achilles’ mēnis, “anger,” is an outsize force which distinguishes him from the average warrior. He becomes an awesome power, to be feared as much by his allies as his enemies. Can we admire someone capable of both incredible feats of valor and acts of savagery? Achilles is defined by his choice of a short, glorious life over a long, safe one. Would we choose the same? The Iliad presents us with several other similarly fascinating characters. Hektor, Achilles’ foe, yet the most noble and tragic figure of the poem, driven by shame to his own destruction. Helen seems aware both of her own beauty and of the infamy she will have in perpetuity for the part she played in launching the war. In our focus on these passages from the Iliad we will grapple with topics important to the poems as a whole and to these sections specifically. We will study the particular features of the Homeric dialect, paying attention to its many archaisms and differences from later Greek. We will learn how to scan the epic meter, including its irregularities. We will study the nature of Homeric composition, including formulas, type-scenes, and borrowings from other traditions. More specific to the books 1, 3, and 6, we will consider why the quarrel begins between Agamemnon and Achilles and what the divine plan for their conflict and for the as a whole war is; why Paris becomes willing to fight and likely die in Book 3, only to be saved from his death ignominiously by Aphrodite; why Diomedes and Glaukos exchange gifts instead of fight. Finally, we will consider how the ethical world of the Homeric heroes differs from and resembles Christian ethics in a modern 21stcentury society.

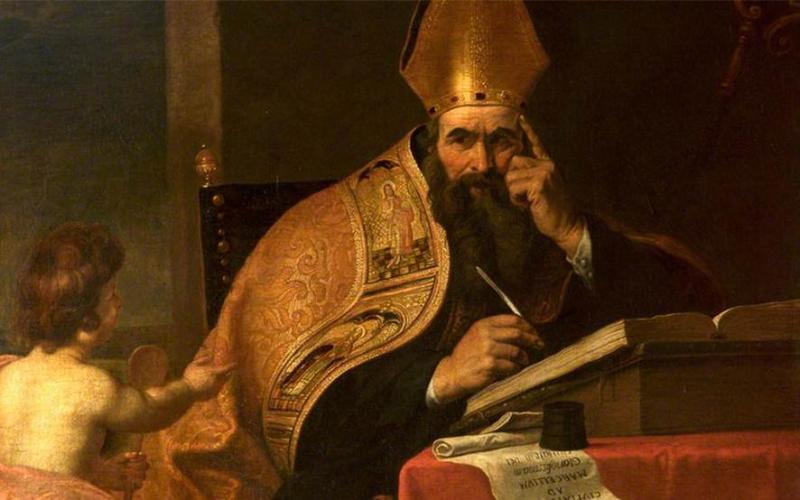

Augustine’s Confessions

Latin 333 (4 Credits)

Fecisti nos ad te et inequietum est cor nostrum, donec requiescat in te.

“You have made us for yourself and our heart is restless until it rests in you. ”Perhaps you have read the Confessions in English, but have you ever wondered what Augustine really said? You’ll never know until you have read it in the original Latin. And if you haven’t read it yet there is no better occasion than this. Join us as we follow Augustine’s restless journey from wayward youth to hero of the faith—and hone our skills at Latin on the most important and influential Christian book ever written in Latin. Come and study Augustine’s revolutionary spiritual autobiography this spring. Tolle! Lege!

Seneca’s Moral Letters

Latin 343 (4 Credits)

Stoicism is having a resurgence. The Washington Post, the Atlantic, and other major media outlets have noticed the trend. In particular, the ethical doctrines of Stoicism are being increasingly embraced for their relevance to our modern anxieties. Perhaps if we remember our deaths we can lead richer lives? Should reason always rule emotion? If events of the universe are out of our hands, how can we have meaningful lives today? In this course we will examine the philosophical writings of Seneca the Younger. Seneca is one of our best representatives of later Stoic philosophy. His letters and dialogues address many perennially important moral topics, including the role of the emotions, our attitude towards death and loss, our duties to others, and the place of fate and responsibility. We will be closely reading 16 of his Ad Lucilium Epistulae Morales in Latin. These, though in the form of letters to a friend, are in fact philosophical essays. In addition, we will be reading a recent scholarly (but highly readable) biography of Seneca, along with a substantial selection of his other works. And in order to properly situate his thought, we will be reading some supporting literature in the stoic tradition that preceded him. The class is tagged PI. Get your philosophy requirement while also enjoying reading in Latin.

The Gospel of Luke and the Acts of the Apostles

Greek 347 (4 Credits)

“In those days a decree went out from Emperor Augustus that all the world should be registered. All went to their own towns to be registered. Joseph also went from the town of Nazareth in Galilee to Judea, to the city of David called Bethlehem . . . . And so we came to Rome. Paul lived there two whole years at his own expense and welcomed all who came to him, proclaiming the kingdom of God and teaching about the Lord Jesus Christ with all boldness and without hindrance.”

Read from beginning to end the Greek text of Luke’s two-volume history of what Jesus “did and taught,” from the forerunner’s birth through the apostle’s proclamation of the good news in Rome. As Koiné texts, these are a natural next-step after 201 and a wonderful way to put down roots in the language. What better way to spend a portion of your semester than to sit at the feet of Jesus and his apostles, watching, listening, and then following?