Sign Posts of Eternity

How the enduring research of eight Wheaton faculty has taught them the inexhaustibility of learning and the heaven-focused impact of their academic contributions.

Words: Jenna Watson ’21

Photos: Josh and Alexa Adams

Dr. Timothy Larsen studies in his Wheaton College office space, lined with bookshelves.

We know them largely for what and how they teach. The English professor who introduced us to T.S. Eliot and Toni Morrison. The biology professor who made research methods come alive in the lab. The anthropology professor who taught us the word “ethnography” then, two months later, watched us present our own. The teaching, inquiry, and transformation that happen in these classrooms is what draws students to Wheaton. And Wheaton faculty love to teach.

But there’s another side to their work, too. In the afternoons after class, in the mornings before students get up, and in the summer months after commencement, Wheaton faculty are opening tabs, writing emails, and starting Word documents related to more than just their teaching. They’re flying to Oxford, driving to Chicago marinas, Zoom calling researchers in Brooklyn, and presenting at conferences in Prague. The students are largely why these professors are at Wheaton, but their research is what got them here. For most faculty, it’s still an enduring, significant part of their life.

More than a handful of Wheaton faculty—far more than represented in this article—have studied their topic of choice for decades, often longer and more deeply than other scholars in their fields. This has put them in the unique place of being, broadly speaking, “experts.” Although experts are formed in many ways, those interviewed for this article have, often after decades of education and research, risen to the top of their field as an authoritative voice on their subject matter. They have published seminal works, become the go-to consultant, or in some cases been the sole person to study their chosen topic.

Expertise is a term that suggests confident command of a topic, yet the term in practice can be more nuanced. To be an expert is to live in paradox: The more you learn, the more you realize how little you know. So it is worth considering this experience and understanding the joys and motivations of how Wheaton faculty devote their life’s work to a single topic or field. It deserves a look beyond the ways students brush against their research in the classroom, beyond the anecdotal illustrations in their chapel talks, and in the context of what it’s like to know something more deeply than most—to have made this research an enduring part of one’s life.

Closing the Gap

Dr. Sarah Borden Sharkey ’95, Professor of Philosophy

For most of the scholars interviewed for this piece, their journey to expertise began with a seed of interest that decades of research cultivated into their present accomplishments. The source of that initial spark varies greatly—from a deep love of a particular text to an identified academic gap for a perceived need in the world.

For Dr. Sarah Borden Sharkey ’95, Professor of Philosophy, one of the sparks that motivated her decades of research on Edith Stein was noticing similarities between Stein’s intellectual journey and Borden’s own. Edith Stein (1891–1942) was a German-Jewish philosopher and Catholic convert who had big, bold ideas about God, individuality, being, gender, and more. She began a promising academic career in philosophy, but due in part to anti-semitic legislation, as well as her status as a woman, Stein never achieved the success for which she was thought to be destined. When she was killed by Nazis at Auschwitz in 1942, she left behind a treasure trove of writing and translation work that has since been collected into 28 volumes.

Although Stein’s life story and Borden’s share few similarities, their intellectual paths are strikingly similar. During her undergraduate studies at Wheaton, Borden became interested in phenomenology, the same kind of contemporary European philosophy to which Stein devoted her early life’s work. Then in graduate school, Borden fell in love with the medieval period, drawn to the questions and concerns of its philosophy. Stein, too, began in phenomenology and drifted to the medieval. When Borden was introduced to Stein in 1997, she was struck by their similar paths and shared intellectual interests.

“I was intrigued because it’s not the most common path in the world,” said Borden, “I wanted to see how she did it.”

Borden resonated with Stein’s intellectual approach to the questions she asks. “She’s always taking positions that are deeply rooted in traditional conversations, but attentive to contemporary concerns,” Borden explained.

What started as this feeling of kinship due to a nontraditional intellectual path has turned Borden into one of the foremost Stein scholars in the English-speaking corner of academia. When Borden started studying Stein, she was one of the few academics doing so. Now, though the scope of Stein scholarship has grown, Borden is an authoritative voice in the conversation, having written the first intellectual biography of Stein, as well as several important studies of her life and writings.

“I want her to be part of the philosophical canon,” Borden said. And this seems to be where Stein is headed. In 2022, Borden was part of a conference in Prague on intentionality and personhood in the writings of Thomas Aquinas, John Duns Scotus, and Edith Stein. “She was a full part of that conversation,” Borden said. “That’s the right direction. That’s what I want.”

Dr. Litong Chen, Visiting Associate Lecturer of Chinese Language and Literature

Like this aspect of Borden’s work, Dr. Litong Chen, Visiting Associate Lecturer of Chinese Language and Literature, was motivated by a desire to bring an understudied topic to greater academic attention. For Chen, this began when he learned of a Chinese dialect that had never been researched or documented. To this day, he is the only known scholar to study this dialect in depth.

When a family friend told Chen of the Dapeng dialect in southern China, Chen, like most people, had never heard of it. “I did a literature review and saw nothing—almost nothing,” he said. “There may be one or two lines in a book talking about this strange dialect, but no one had done any in-depth analysis.”

So Chen did. He applied for grants and embarked on summer-long fieldwork. “I studied, I recorded the dialect, and I lived with local people,” he said. “I spent time with them and made friends. I observed not only their language, but their language use.”

Nestled in the province of Guangdong, China, across the strait from Hong Kong and difficult to access, the Dapeng peninsula was historically isolated from major languages. This allowed the dialect to develop with little outside influence. It is spoken by only several thousand people, which intrigued Chen but also motivated him to preserve it. “I wanted to make sure we knew something about it before it’s gone,” he said.

Chen has now witnessed the resilience and vitality of the language, as well as comprehensively documented it, so he is less concerned about it dying out. Still, he is motivated by the belief that no dialect is too small to care about. Of course, he said, “you always want to do something that has never been done before.” But beyond that, he believes that all people have the right to speak their own language. He does not want this one to die out merely because no one cared enough to study it.

“I hope that these kinds of dialects will be recorded, archived, and documented,” said Chen, and he is doing just that for Dapeng through an online archive with the University of Hawaii. In fact, in the summer of 2022, Chen brought this project even closer to home when he launched the second phase of his research: visiting Chinatowns across the U.S. to record the spoken dialect by Dapeng immigrants and their descendents. Chen sees this effort as an opportunity to preserve the cultural heritage of Chinese Americans and celebrate the cultural diversity of the U.S. through this little-documented dialect.

Dr. Kristen Page, Ruth Kraft Strohschein Distinguished Chair & Professor of Biology

Dr. Kristen Page, Ruth Kraft Strohschein Distinguished Chair & Professor of Biology, was also partially driven by the desire to fill an academic gap and motivated by care for those impacted by this lack of study. Page began her Ph.D. intending to study mid-sized predators, but she soon learned of a parasite called Baylisascaris procyonis found in raccoon feces. This parasite, if unknowingly consumed by children who find and eat these innocent blueberry-looking piles in their yard, can be fatal or cause lifelong neural damage. The roundworm is also deadly to small mammals such as the Eastern woodrat. In fact, when Page began studying the parasite, it was nearly killing them off completely.

“Nobody had ever looked at the ecology of this parasite before,” said Page, “Even though the parasite had been studied since the 50s, it was only studied on the medical side.”

The scholar who was regarded as the academic expert on this parasite, Dr. Kevin Kazacos, became Page’s second Ph.D. supervisor, and when Kazacos retired, the title of “expert”—or at least one of them, Page humbly insists—shifted to Page. For this reason, Page is now the one a concerned mom in Chicago might call if she has discovered one of these deceptive piles in her backyard, fearful that her child has contracted what can be a life-altering or fatal disease.

Thanks to the work of Page, Kazacos, and others who are getting the word out about this parasite, there have been fewer and fewer fatalities and cases of brain damage. And while care for child safety and public health greatly motivates Page, she is also driven by care for small mammal populations.

Even more often than concerned moms or public health officials, Page’s expertise is summoned for conservation efforts. Most of her work on Baylisascaris is in studying its transmission and the use of mitigation strategies to preserve small mammal populations, such as the Eastern woodrat. Departments of Natural Resources in New Jersey, Ohio, and Indiana all depend on Page and her students for running samples to test baiting success. And thanks to the collective efforts of state conservationists, a group of scholars, and Wheaton students helping Page run samples, parasite cases appear to be down and woodrat population expansion appears to be up.

Dr. Nadine Rorem, Professor of Biology

Down the hall in Wheaton’s Department of Biology, there’s another expert in the house. Dr. Nadine Rorem, Professor of Biology, wasn’t planning to become an expert on the hydroid cordylophora. She wasn’t planning to research much at all. In fact, she wasn’t even planning to get her Ph.D. She just wanted to teach.

“I came from a family where few people had a college degree,” she said. “But I fell in love with serving college students and I wanted to teach them. I love that interaction and those relationships. So it was somewhat by default that I would get a doctorate, just so I could go on to teach college students.”

Rorem’s fascination with cordylophora began because it was so teachable. This tiny freshwater animal, which looks like “a little baby sea anemone,” is a “perfect model for teaching students how to conduct research and design experiments.” For this reason, Rorem has been studying cordylophora for close to 30 years, even before she started teaching at Wheaton in 1993.

Although Rorem’s academic journey has been driven more by a desire to teach than a desire to research, the two gradually became mutually enriching, and she now finds herself loving the research portion of her work. She also finds herself with a status she never thought she would have: expert.

“You know,” she said with a smile, “when you find an obscure critter, sometimes there’s merit in that because no one else really has put time and energy toward it. And then all of a sudden, by default, you’ve become an expert on it.”

Google the hydroid, and you’ll see Rorem’s research. Her photos populate the taxonomic databases, and her name often leads the bibliographies. When power plants need to have cordylophora removed from their intake filters, Rorem is the one of the first people they call. And after 30 years, she is so intimately acquainted with the little invertebrates that she can walk up to a marina and sense if they are there.

Still, the first and fullest joy of her research is the students she works with. “The Lord has really woven the research and the mentoring so closely together, in a way that’s been sort of the footprint of my time at Wheaton,” Rorem reflected “And I’m just really grateful for that.”

The Experience of Expertise

When it comes to the scholars whose stories are told here, the motivations for academic research are many, and what sustains them day by day or year by year may change. Interests deepen, side projects form, ideas percolate, and books are written. Many of them are now three or four decades into their academic pursuits, after that initial spark. So what’s it like now? Now that their name is attached with authority to a particular topic, what does academic expertise feel like?

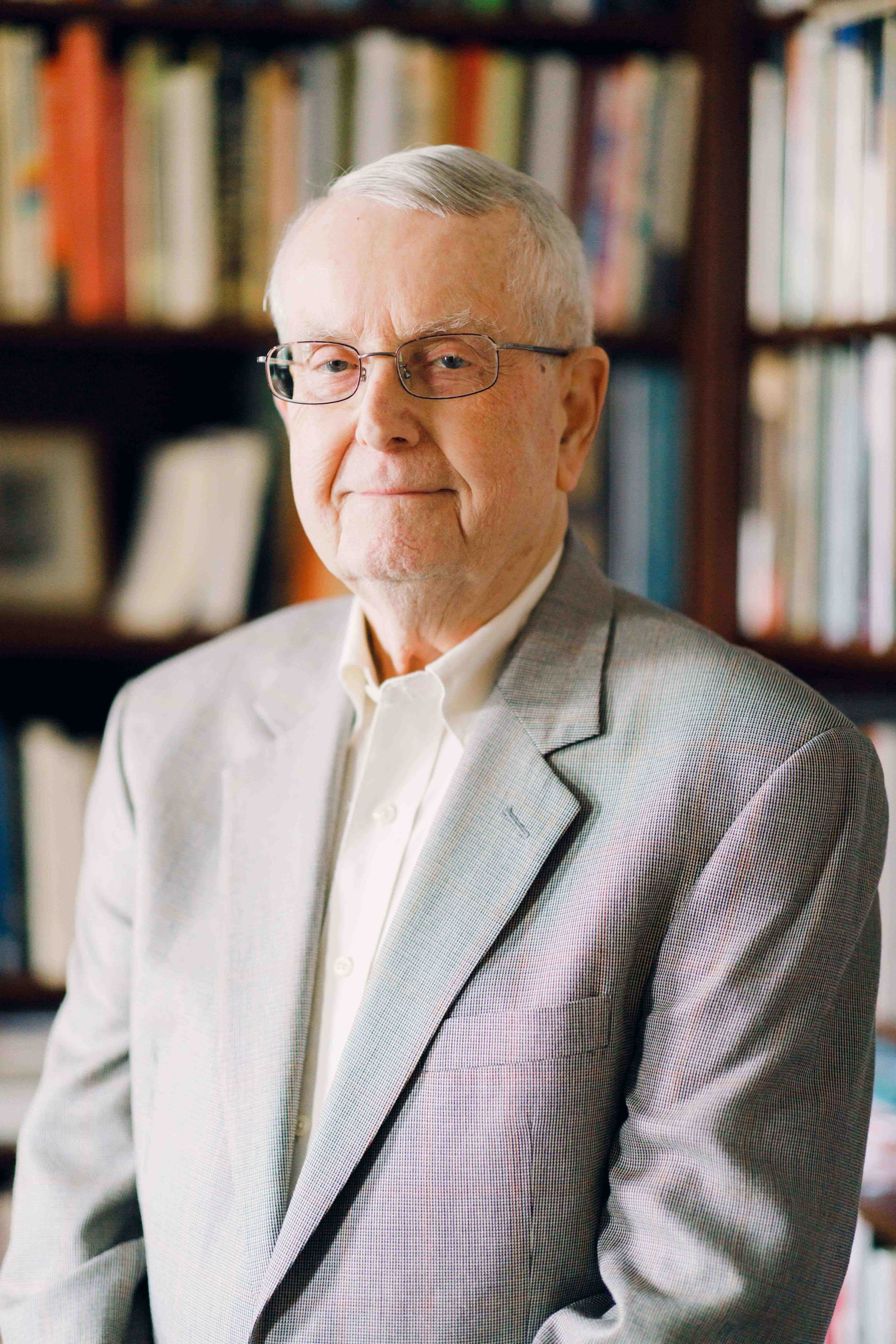

Dr. Timothy Larsen, Carolyn and Fred McManis Professor of Christian Thought and Professor of History

It turns out when you’ve studied something for decades, people get flustered to talk about it in your presence. At least, that’s what Dr. Timothy Larsen, Carolyn and Fred McManis Professor of Christian Thought and Professor of History, has experienced. Having studied theology and religious history for decades, written and edited authoritative texts in his discipline, and taught at Wheaton for 20 years, he is the one to whom pastors turn mid-sermon with a fearful, “Is that right?”

“I just want to be an ordinary person in the congregation,” he said with a chuckle. “But pastors get it in their heads that I know lots of stuff and they’ll suddenly be worried that what they’re saying isn’t true.”

It’s reasonable to assume that Larsen can sniff out heresy. With advanced degrees in history, theology, and historical theology, Larsen’s CV is extensive. He has written most consistently on faith and politics in Victorian England, with significant forays into the history of evangelicalism, women in ministry, the history of the Christmas holiday, and more. He has edited authoritative texts on evangelicalism, including The Cambridge Companion to Evangelical Theology and The Biographical Dictionary of Evangelicals. A few threads that tie his work together, he explains, are that most of his research is about the history of England, and most of it is about areas where Christianity or its reception has been misunderstood by scholars.

For example, Larsen has sought to correct the dominant academic discourse about nineteenth century England that there was an almost total loss of faith, presenting as counter-argument the stories of many important thinkers who were having not crises of faith but crises of doubt—as in, they were realizing that Christianity was harder to doubt than they thought. Or, more recently, Larsen ventured into the history of anthropology, a discipline that has often been perceived as undermining the Christian faith. Once again, Larsen presented the stories of some of the most influential anthropologists who in fact had articulate and compelling reasons for their commitment to both Christianity and anthropology.

“My academic projects started with Christianity and politics, and then I kind of went from there,” he explained. “I was always looking to do a kind of ‘Christianity and ____’ project. And in the end it would often be an area where Christians are misunderstood, or in which there is an intellectual challenge to Christianity.”

So while it’s not surprising that he would give pastors pause when he’s sitting in their congregation, Larsen admits he has also felt the same thing. “It kind of gets in my head, too,” he said. “Sometimes I preach in Chapel at Wheaton, and I realize, ‘I’ve got Old Testament scholars in the room, and I’ve got an Old Testament text. I hope they think I’m handling it right!’”

To be an expert, then, means you can’t just switch your expertise off, even when you’d prefer to be an anonymous face in the crowd.

To be an expert is also, of course, to carry deep familiarity with one’s subject matter. Borden describes the fruit of this familiarity as a kind of intellectual sharpening: “I feel like much of my life is like, ‘What would Stein say? Well, I’m not sure if I agree with her—but you know, maybe she’s right?’” she said. “It helps me as a thinker to continually fight with her.”

Larsen, too, says he has studied some historical figures so deeply that he feels that he knows them. Any new information that might be discovered would almost certainly fit within his current understanding of their life and work.

Dr. C. Hassell Bullock, Professor of Hebrew Bible Emeritus

Photo by Diana Sokolov Rowan

For Dr. C. Hassell Bullock, Professor of Hebrew Bible Emeritus, more than 40 years studying the Psalms have given him particular closeness with the texts that can only come from decades of immersion. And still, he has never tired of studying the Psalms.

“The older I get, the more the Psalms mean to me, because they are the expressions of the realities of life, the realities of faith, the realities of death and suffering,” Bullock said. “I find that they continue to say things to me that maybe I couldn’t have heard two or three decades ago.”

Forty years of studying something opens one’s eyes to new layers of meaning, according to Bullock. For example, God is said to laugh just three times in the Psalms. To Bullock’s knowledge, though, no one has ever addressed this. All this study has also increased Bullock’s confidence to make new claims and enter uncharted academic territory. So he is including a chapter on the laughter of God in his forthcoming book, Theology from the Psalms: The Story of God’s Steadfast Love (Baker Academic, October 2023).

“That’s the kind of thing that sometimes comes out of your study, when you reach a level where you feel like you could say things that you might not have been able to say at an earlier stage,” said Bullock.

But he is quick to clarify that no matter how many decades of expertise you have under your belt, you are always still dependent on other thinkers. This, too, was a sentiment expressed by others: Even expertise does not mean complete academic independence. Rorem and Page depend on the students in their labs and the academic experts that went before them, for example, and Borden is encouraged by a growing group of emerging scholars studying Stein.

“You never come to the place where you can work independently of everybody who engages in that discipline,” said Bullock. “We need other people to review and sometimes correct what we say. It’s one of the really rich features of academia.”

Even 40 years of expertise does not mean you can go it alone. For Bullock, that is a gift.

Dr. Leland Ryken, Professor of English Emeritus

What the Psalms have been to Bullock in terms of academic specialty, John Milton has been to Dr. Leland Ryken, Professor of English Emeritus. And like Bullock with the Psalms, Ryken has been immersed in Milton for decades. He sees his work on the Puritan writer of Paradise Lost as “the thing that has given [him] a more specific professional identity.” Milton’s works were the focus of Ryken’s dissertation, many books and articles, and countless semesters of teaching during his 54 years at Wheaton.

Also like Bullock, decades of research have caused Ryken’s interest to deepen, not wane. He finds himself continually learning from a text so rich with layers of meaning. And despite this richness, Ryken says, “I read Milton in the same ways and with the same excitement that I first did in 1964 in Eugene, Oregon.”

Ryken articulates the type of textual intimacy that Borden and Larsen also referenced, and recommends choosing one author or work as a lifelong specialty, “getting to know that author’s life and corpus as thoroughly as time allows,” as he writes in Credo Magazine. He adopts this idea from a writer named Charles Osgood, whose advice was specifically for Christian ministers. But Ryken recommends this approach to anyone looking to be deeply formed.

“Milton himself defined the effect of Christian poetry in this way: ‘It sets the affections in right tune,’” Ryken said. “Well, that’s what Milton’s poetry has done. It has set my affections and my orientation in tune with God and godly living.”

Although Ryken “could study [Milton] indefinitely,” he does not study Milton exclusively. In fact, Ryken is perhaps best known for his prolific writing on the Bible as literature, biblical translation, Christian approaches to literature, and other topics that comprise his 62-book oeuvre. He recalls a time when he made a definite choice to write and publish outside of his specific academic specialty. He was attending a conference on campus, and he had a moment of realization that he was a writer as well as an academic. He needed to devote time to both, and so he turned away from the conference and walked up the hill to his office in Blanchard Hall. He has followed that decision of academic and authorial balance ever since, publishing across a variety of topics that may or may not fall into the jurisdiction of his early academic training but about which he nevertheless has accumulated expertise.

“I have not carried any burden of anxiety about whether I am ‘publishing in my field,’ which is just a cliché in the academy,” he said. “I have entered pretty much every open door in my writing career, and it has been a great experience.”

Dr. Amy Black, Professor of Political Science

Thankfully, academia has space for the keepers and distributors of highly specialized knowledge, and it also has space for those who feel called to translate their research for the masses. The freedom to do both is one of the distinctives of teaching at a place like Wheaton, according to Dr. Amy Black, Professor of Political Science.

Black grew up in a household where talk of politics and current events was simply in the air. Her family would gather around the TV to watch the State of the Union address. She volunteered for her first local campaign when she was 11 years old. When a family friend ran for state Senate, her entire family helped out with his campaign.

“I thought every family watched the State of the Union together,” she remarked with a laugh. “I learned later that’s not the case.”

Fast forward a few decades and with some experience on Capitol Hill and a Ph.D. later, Black found an opportunity to teach the importance of politics to those who did not grow up in families like hers, where current events were always a welcome topic. She was invited to teach an adult education class on Christianity and politics at her church, and realized on her first day that there was a great need for a Christian framing of the American political system and its most pressing challenges in a way that went beyond party lines. Someone in that church class pulled her aside, and said, “You need to turn this into a book.”

That’s how Beyond Left and Right (Baker, 2008) came to be, and it’s how Black realized that she loved the challenging task of translating her academic work for the masses. This type of translation work can be challenging for many scholars, but Black found that she loved it.

“I decided my goal was to do an academic project and then do something that more serves the church,” she explained, echoing a similar balance to Ryken’s. Today, Black has become a sought-after voice from both academic publishers like Cambridge University Press and Christian publications like Christianity Today.

Several Wheaton faculty are widely known outside the Wheaton community for their writing in the New York Times, Christianity Today, and other major publications. And they have all had to navigate the difficult task of making highly specialized research understandable to the average reader who, as Black describes, is engaged and committed to learning but hasn’t had opportunities for in-depth study of a particular topic.

“We’re in a really special place as faculty at Wheaton,” said Black, “because we can speak to our academic guilds, but we can also use the knowledge that we’ve developed to serve the church.”

Pointing to Eternity

Rowan Williams, former Archbishop of Canterbury and widely published author, once wrote, “To know something is to become alert to God’s outreach within it.” While the experiences of Wheaton faculty are diverse, and their research varied, one commonality is that their research is formative to, and deeply formed by, their Christian faith. Although some have chosen to write broadly and others have focused on one subject, these faculty know what they study. They know it deeply, intuitively, even viscerally, as when Rorem walks up to a marina and senses intrinsically whether cordylophora are there. And for those who believe that truth found in this life is a foretaste, a sign post pointing toward heaven, to study something so deeply, for so many years, is an inevitably formative experience.

Yet while these faculty might know God’s outreach within their subject matters more than most, they are the first to say that they will never plumb the full depths of their research. And perhaps these two things go hand in hand.

“I don’t think it’ll ever run out,” Page said of her studies. “The only way you ever run out of questions is when people lose interest.” Rorem agrees that in science, “you never really arrive at figuring everything out.” But that’s part of the joy, not just in science but every discipline. “The fun is not being an expert, but becoming an expert,” said Larsen. After all, as Borden observes, “You don’t dedicate your life to a project unless it’s bigger than your life.”

What Bullock says of the Psalms seems to be true of academic pursuit in general: The very inexhaustibility of these topics seems to be a glimpse of the eternality of things.

“The Psalms are so multi-layered in terms of meaning and emotion that we will never plumb their depths,” he said. “I have acknowledged that my research attempts to plumb some of those layers but it will never reach the bottom layer. There is no bottom layer. It just tapers off into eternity.”