Pain Redeemed

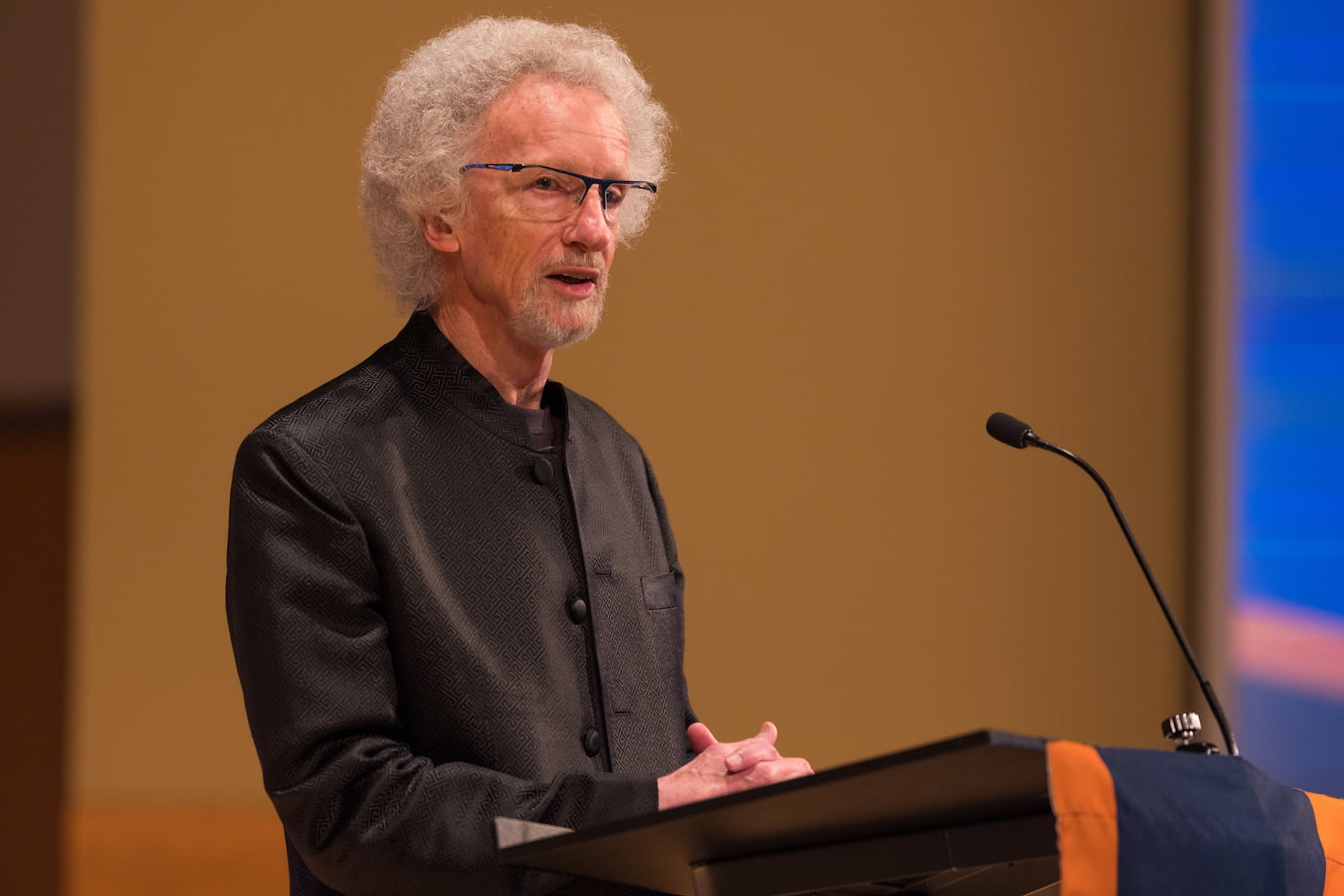

Philip Yancey’s Remarks upon Receiving the Wheaton College Alumnus of the Year for Distinguished Service to Society Award

Words: Philip Yancey M.A. ’72

Photos: Mike Hudson ’89

Philip Yancey M.A. ’72 receives the 2020 Alumnus of the Year for Distinguished Service to Society award from Dr. Beverly Liefeld Hancock ’84, President of the Wheaton College Alumni Association Board of Directors.

On April 1, 2022, the Wheaton College Alumni Association honored Philip Yancey M.A. ’72 as its 2020 Alumnus of the Year for Distinguished Service to Society, after postponing the 2020 event due to COVID-19. Known for his curiosity, honesty, and extraordinary leadership, Yancey is a best-selling contemporary Christian author and speaker who has impacted millions of people worldwide. His highly relatable style of writing, leaning on stories and his journalistic eye, allows him to connect with readers on issues of pain and suffering, faith and doubt, grace, and the life of the church. His books have sold more than seventeen million copies in English alone, and have been translated into over 50 languages.

Upon receiving his award at the April 1 event, Yancey shared an address with the College. The following transcript of his remarks has been edited for clarity.

I feel like I’ve just sat through my funeral, with one exception: I get a rebuttal. Until about an hour and a half ago, I thought this whole thing may be an April Fool’s joke. I’m glad you quoted [the sportswriter] Red Smith, Dr. Ryken: “It’s easy to write a column; you just open up a vein and let the blood flow.” And I did that in the memoir, Where the Light Fell, that the Alumni Association has graciously provided for everyone here. That’s a tremendous gift and a gutsy gift, Cindra. It’s not a typical, fairytale happy Christian memoir. It’s my lifeblood.

It’s an irony to be honored for distinguished service to society because I sit in my basement office and type on a keyboard all day. I write about justice, and I write about racism, and I write about Ukraine. But I do it vicariously. It encourages me to hear that, to paraphrase John Milton, they also serve those who only sit and click.

Early in my career, I wanted to be an investigative reporter. This was the era of Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein. These were our role models. And I thought, “Wouldn’t it be great to do that in the Christian world, to expose those frauds and bring them down, expose their hypocrisy?” I tried that for a little bit. Then I decided I didn’t want to spend my life doing that because I had to hang around jerks all day—the jerks I was writing about. So, I decided instead to shine a light on servants that others hadn’t noticed—people who served Christ and His Kingdom.

I owe a lot of thanks to people along the way. To Harold Myra, who took a chance on a damaged, unformed me with no real experience. My portfolio at the time consisted of cutting out with scissors, pastings from a college newspaper. That was it. Harold gave me my first and only job, the only regular salary check I’ve ever had. First at Campus Life and then when it merged with Christianity Today. Thanks also to Dr. Paul Brand LL.D. ’71. (All of these have a Wheaton connection: Harold was teaching here; Dr. Paul Brand’s daughter Pauline was a student here.) No one has impressed me more than Dr. Brand. He taught me the truth of the statement by Jesus recorded more often in the Bible than any other—six times. It goes something like this, and I’m paraphrasing: You don’t gain your life by acquiring more and more. You gain your life by giving it away and ironically, in the very process of doing so, you gain it. Dr. Brand was offered Head of Orthopedic Surgery at Stanford University and at Oxford University. He turned them both down to serve among the lowliest people on the entire planet: people with leprosy in the untouchable Dalit class in India. And he found his life in the process. In a period of time when I would have been unable to write about my own faith—because I was still in recovery from the fundamentalism that you can read about—those 10 years collaborating with Dr. Brand gave me a cocoon period to develop. I remember speaking at his funeral, and I said we had a strange exchange, Dr. Brand and I. I gave words to his faith, for he’d never written much. I gave words to his faith, but in the process, he gave faith to my words, because I could write about him with integrity before I could write about myself.

And I think of so many of you here today. Our friends, Jonathan ’83 and Beverly Hancock ’84, Ken and Lee Phillips ’77, and Scott ’73 and Jill Bolinder ’74 (who drove over here from Grand Rapids just for this evening). They and many others taught me what normal, healthy Christians are like: people who are made larger by their faith, not smaller. I knew many of the other kind. In the process we also found a church. LaSalle Street Church—and many of you share that experience; some of you met your spouses there—became a spiritual home for me, a place that actually lived out what Jesus commanded us: to bring together, in unity and diversity, people of different races and incomes and beliefs.

Finally, Janet, who took a chance on a wounded redneck from a trailer park. She became a social worker and hospice chaplain. Every single time I’ve had a book signing, no matter the country, there’ll be a line of 100-200, and sometimes more, people. Always, someone will come up to me and say something like, “I lost my three-year-old son last week,” or, “My 18-year-old daughter died of a drug overdose,” or, “I learned yesterday I have breast cancer.” I can’t say, “Oh, I’m so sorry... Next!” Instead, I say, “I’m so sorry. I want to hear the whole story but there’s a long line of people. Would you mind talking to my wife? She’s actually trained to hear your story. And she’ll tell me everything you said.”

In 50 years as a journalist, I’ve learned one thing: Life is unfair. Some of us are stewards of pleasure and success. Some of us are stewards of pain and failure. I’ve learned that pain redeemed impresses me more than pain removed. We always want the latter. But the people I’ve gotten to know, the people I’ve interviewed, the people I’ve profiled, teach me that lesson: Pain redeemed impresses me more than pain removed.

I’ve experienced that in my own life. When I wrote my memoir, at the end of the book, I said: I felt like I was putting together a jigsaw puzzle, with no picture on the cover. But when I finally put it together, it was clear that the themes of my life, the themes of my books, my words, are suffering and grace, those two things. I spent about 20 years under law—extreme law. But I’ve spent 50 years under grace. And what I’ve found is that the pain has been swallowed up by grace. Nothing goes wasted. God can take those things we don’t want, and out of them create something we can’t imagine.

I’ve been a freelance writer, which is a good role for me, out of my suspicious, skeptical background, wounded by the church. I’ve never had a board I had to report to. I’m not ordained. Nobody can fire me. I’m free to explore issues of faith as an ordinary pilgrim in the pew, tilted toward the doubters. I’ve been blessed to be able to reconstruct my faith in public and make a living at it.

President George W. Bush used to talk about an axis of evil. I grew up in an axis of fundamentalist insanity. But I found an axis of evangelical sanity—people like Wheaton, Intervarsity, Billy Graham ’43 Litt.D. ’56, John Stott, Fuller Seminary. And Wheaton, we need you in these divisive times. The word “evangelical” is increasingly becoming a bad word. But it’s one I still cling to. I was with Walter Kim, of Korean descent, who’s head of the National Association of Evangelicals. He had just returned from a conference. I think there were 70 countries involved and only one person was invited from each country, so only one American among the 70. They ganged up on Kim and said, “We understand ‘evangelical’ is a bad word in the United States. Well, it’s not where I live. When you say that word in so many countries, it brings to mind clinics and hospitals and people fighting sex trafficking and orphanages and educational institutions. You can trash the word if you want to, but we’re keeping it because it means good news.”

Here in the United States, we’re so media-driven. Mostly that word has a political connotation. It’s a lens. It’s an either-or: Which side are you on? The center in divisive times is so hard to hold. When you build a bridge, you get walked on from both sides, as people at Wheaton know.

We need not an either-or faith; we need a both-and faith. John said that Jesus came full of grace and truth. A lot of people work hard in the truth department. Some people work hard in the grace department. Few people I know work hard in both. We need people who combine unity and diversity, as Jesus taught us. Evangelicals haven’t done that very well, historically. We need someone to show us the importance of both action and contemplation, the importance of this life, and also the importance of the next life, in a floundering culture that keeps widening the gulf between them.

Philip Yancey M.A. ’72, delivers his remarks to Wheaton College on April 1, 2022.

Wheaton, President Ryken, may you not water down the radical gospel, while also equipping people to live their ordinary lives. Teach us how to be the church that Karl Barth called the “sign of contradiction” that shows a different way to thrive while opposing the false messages of our secular culture. Wheaton, keep pumping out culture shakers and also culture shapers. We need both. We need those who shake us, make us wonder—“What is that sign of contradiction? Why are we here? And what are we meant to do while here?”—while also creating and shaping a society more just, more pure, more beautiful. Do this not because you have all the answers but because in humility, you know that you don’t. It’s part of Wheaton’s heritage.

David Brooks (who has a Wheaton connection, his wife) went to the University of Chicago. This is how he describes that school: “The University of Chicago, founded by Baptists, is a place where atheist professors teach Jewish students how to read St. Thomas Aquinas.” I have a degree from the University of Chicago, and I remember riding the elevated train down there to a pretty sketchy neighborhood. And when I would get there, I would sometimes go into the Rockefeller Chapel built by Rockefellers—this magnificent Gothic structure. I would study whole courses on John Donne, on George Herbert, on T. S. Eliot, W. H. Auden—all deep-thinking Christians. But before I got there, I would pass storefront churches: Beulah Land Today Missionary Church, The Holy Spirit of Brotherhood Church of God in Christ, Water in the Rock Baptist. Our faith encompasses both: the people I was studying and also those storefront churches with maybe 30 or 40 people who would show up and express their faith together.

Wheaton will turn out bankers and doctors and ambassadors and leaders; you’ve done that for years. But you’ll also turn out people who will work for the Humanitarian Disaster Institute and serve the poor and attack racial injustice. It’s a both-and faith. Keep that up. Jesus spoke two ways. To the oppressors, he called out greedy landlords and corrupt politicians and religious hypocrites. But he didn’t say to the oppressed, “Workers, throw off your chains.” No, he said, “Blessed are the poor. Blessed are those who mourn. Blessed are the persecuted. You have a different, more lasting reward.” He too seemed more impressed by pain redeemed than pain removed.

Two weeks from today, we’re going to remember a tragic event: the worst thing that ever happened in human history, the execution of God’s own Son. It’s a day that we call Good Friday. Pain redeemed, not pain removed.

You may have seen a week or so ago, the very brave Russian TV editor, who in the middle of a broadcast on “the great victories in Ukraine” appeared with a sign that said, “Stop the war, stop the war” on live TV. She was echoing a true event that happened in 2004, the original Orange Revolution in Ukraine. There was a Russian-backed candidate running against a very brave man Victor Yushchenko. Everyone knew Yushchenko had won; he had an 11 percent lead in the exit polling. Yet that night on Russian television they announced: “The challenger Viktor Yushchenko was decisively defeated” (by the Russian-backed candidate).

They hadn’t counted on a brave woman named Nataliya Dmytruk, who did sign language for the deaf. In the lower right-hand corner of the TV screen, while they’re announcing the great victory of the Russian-backed candidate, she signed, “They stole our election. They’re lying through their teeth. Come to the Maidan Independence Square tonight in protest.” Deaf people started the Orange Revolution in Ukraine in 2004! They showed up that night—100,000 strong—and the crowd kept growing: 500,000, a million, ultimately two million people, a fifth of the population surrounding Kiev. That started the Orange Revolution.

We Christians don’t control the media. When we do, we usually mess it up. But we have a message in the lower right-hand corner of the TV screen: that “sign of contradiction” for a culture that tells us what matters is celebrity and success and wealth and power and entertainment and indulging. “They’re lying through their teeth.” There’s a different story, a different One to follow. And the only way the larger world is going to know that is, if we are indeed a “sign of contradiction.” Thank you, Wheaton, for being that sign of contradiction. Thank you for being a pioneer settlement of the kingdom of God. Thank you, Wheaton, for fulfilling that in my life. Amen.

Wheaton, keep pumping out culture shakers and also culture shapers. We need both. We need those who shake us, make us wonder—‘What is that sign of contradiction? Why are we here? And what are we meant to do while here?’—while also creating and shaping a society more just, more pure, more beautiful. Do this not because you have all the answers but because in humility, you know that you don’t. It’s part of Wheaton’s heritage.