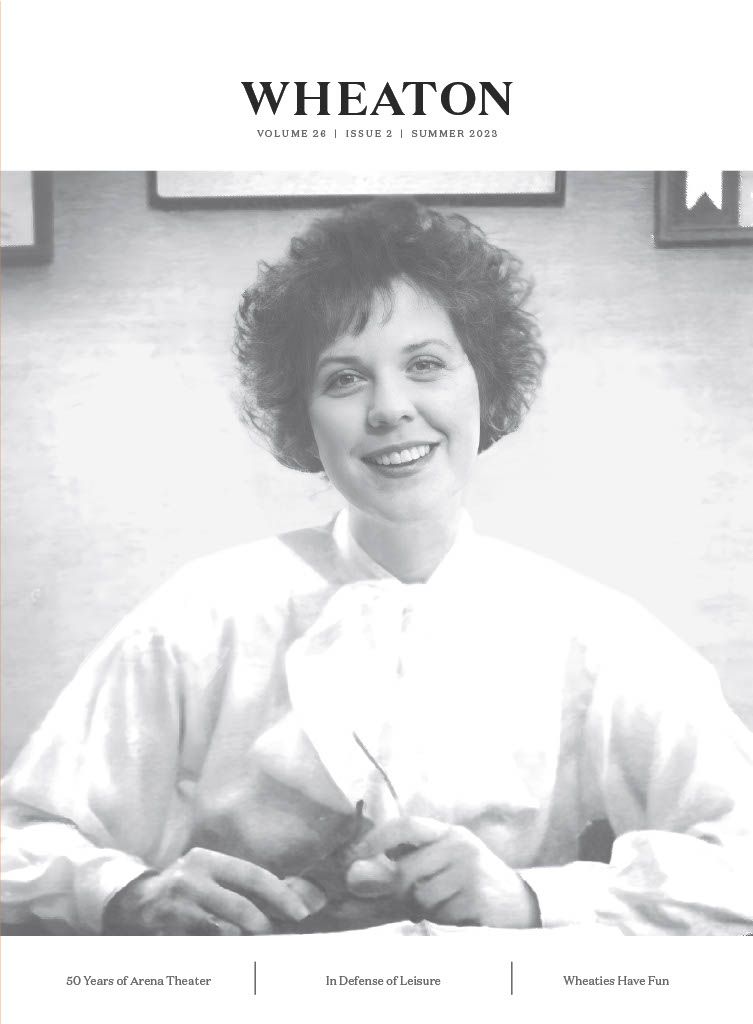

Fifty Years of Arena Theater: The Prologue

Words: Cassidy Keenan ’21

Photos: Tower Yearbooks and Wheaton College Archives & Special Collections

Editors’ Note: In the Summer 2023 print issue of Wheaton magazine, we published an article titled, “50 Years of Arena Theater.” Following that feature’s release, we found still more pieces of history and central voices that carried Arena Theater on their shoulders throughout the decades. Although it would take a lifetime to hear and share every contributing narrative, this prologue seeks to fill in some of the stories we weren’t able to tell in the original feature.

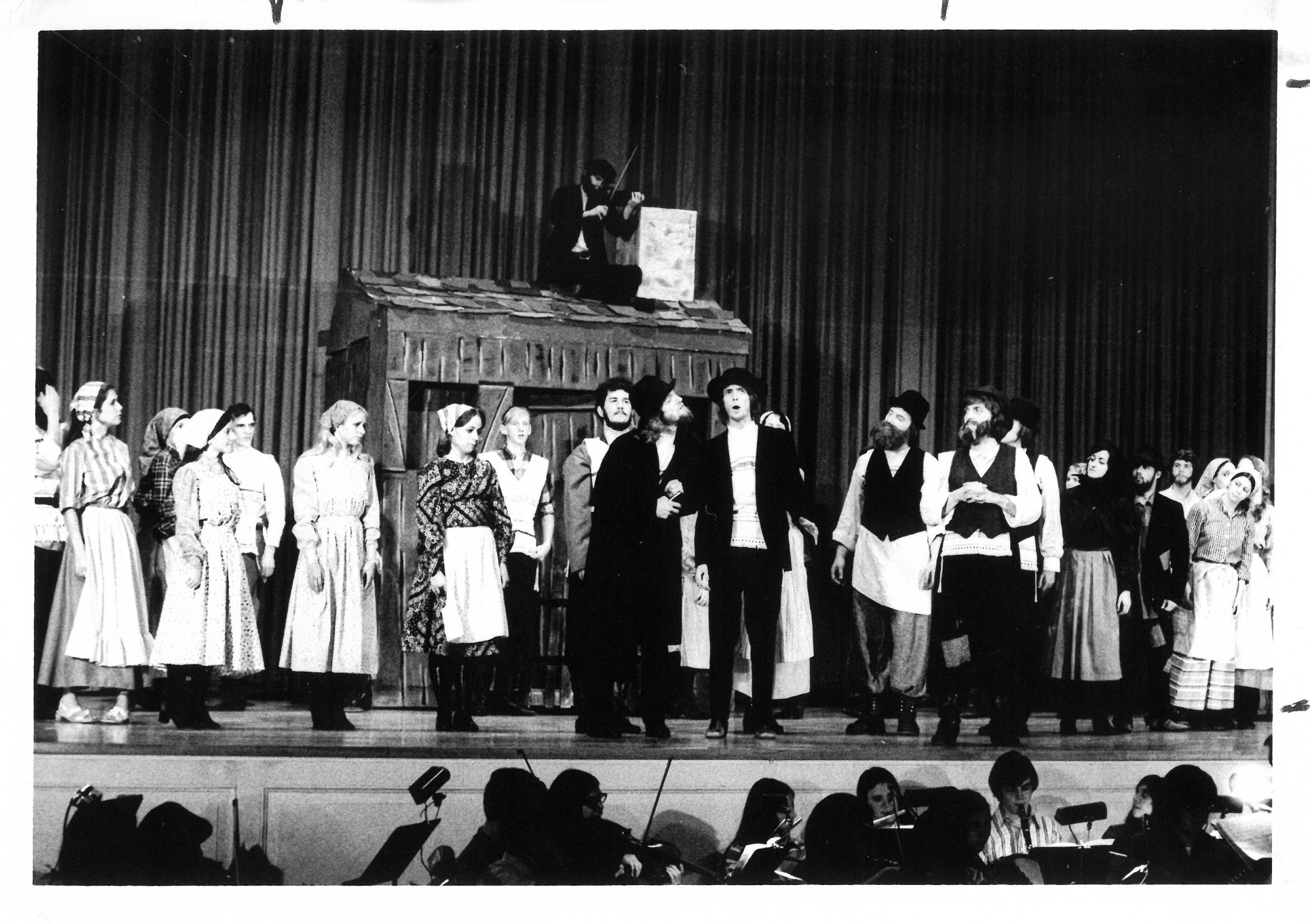

Student production of “Fiddler on the Roof”

1972

Every good story has a beginning. Here in the fall of 2023, we are celebrating the 50-year anniversary of Wheaton College Arena Theater, and earlier in the year, I had the privilege of telling part of this story. Through interviews with friends, alumni, and directors, extensive research in the archives, and rifling through some of my own most precious memories, I pieced together a narrative that extends all the way back to 1973—five decades of drama at Wheaton College. 1973, I wrote, is where it all began.

For the purposes of celebrating 50 years, this is true enough. However, every good story also invites intrigue about events outside the timeline, hence the popularity of prequels and sequels. Since Arena’s story continues, Lord-willing, I am unable to offer insight into what happens after “The End.” But as I discovered, there is a full, rich, and compelling history before “The Beginning” ever really took place. More research, more interviews, and less of my own memories this time led to one very apparent conclusion—one that I had hardly realized before. Drama existed at Wheaton College in many different forms long before 1973.

I invite you to enter into this prologue with me as I do my best to tell another impossible story. There are new heroes I am eager to introduce, who overcame opposition the likes of which I have never known in order to establish and preserve the now-beloved drama program. Thanks to them, I have witnessed some of the most incredible storytelling of my life. I’m sure anyone who went to see the most recent Shakespeare in the Park pre-performance puppet show would say the same.

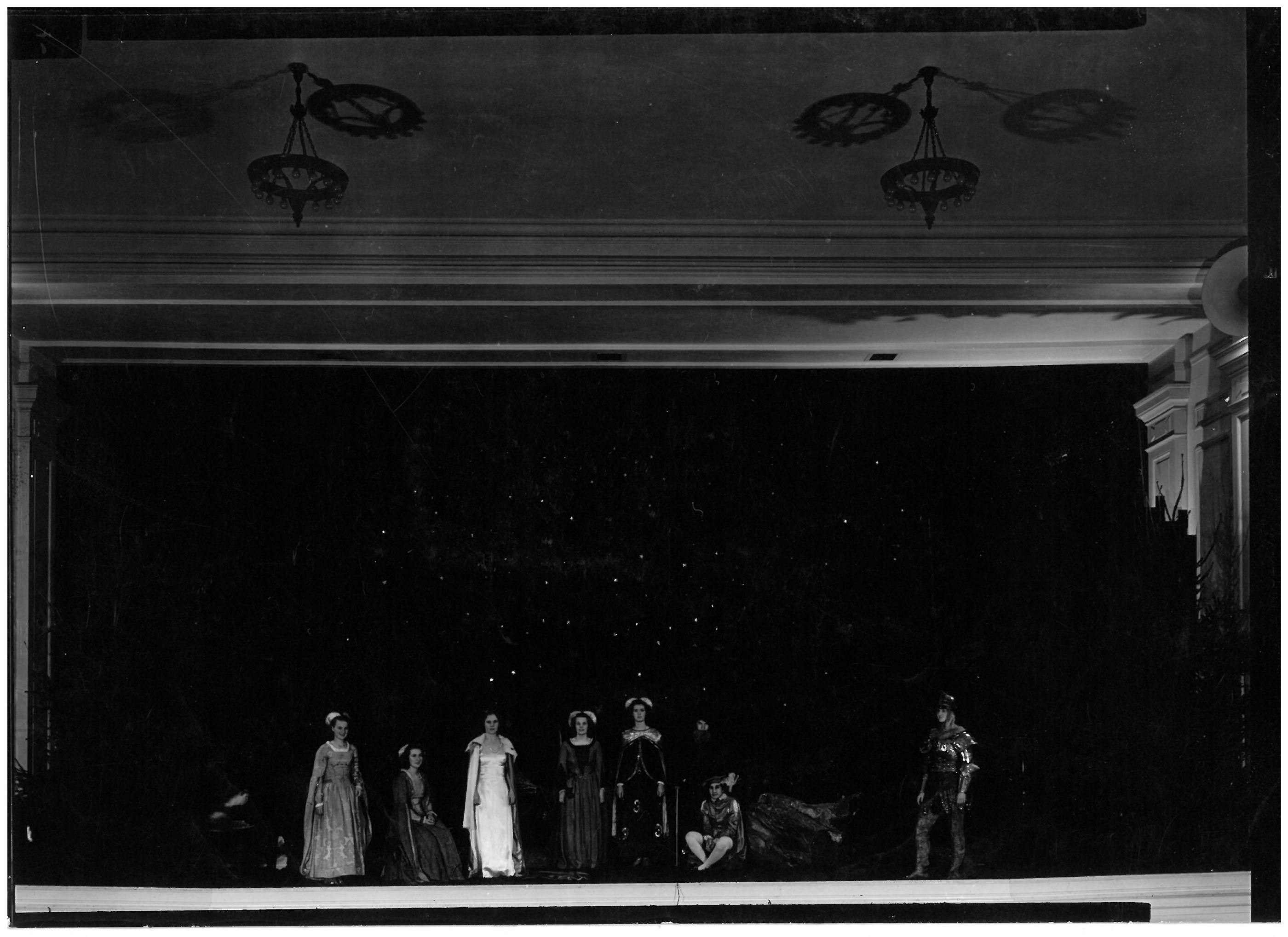

An early student-initiated theater production in the 1950s.

In tune with the overarching fundamentalist climate of the time, theater was officially strictly forbidden at Wheaton College in the early 1930s, 40s, and 50s. In any early document, “drama,” whether it be stage, film, or television, is written about with all the shock and condemnation that one might use to describe someone tap dancing on the Bible. A memo from the Drama Committee’s meeting with the College’s administration in 1954 reads, “Dr. [A.W.] Tozer is completely opposed to all Christian drama (movies). He feels that the devil, unable to make a frontal attack, is coming in at a side door via this means.” Regarding television, they simply wrote, “He is much afraid of TV; says he has no set and thinks TV will do much harm.” Tozer, who pastored a church in Chicago at the time, gave several Chapel addresses in the 1950s and often corresponded with Dr. Raymond C. Edman, who then served as Wheaton College’s president.

However, even with this strict stance, dramatic performance was already beginning to flourish at Wheaton in unconventional forms. One of the most notable of these were the literary societies, which existed at Wheaton as early as the winter of 1854–1855. There were four major societies in total—Beltonian, Excelsior, Aelioian, and Philalethean—and they served an enormous social and dramatic purpose on campus. Not only did they provide “loyalty without clannishness, brotherhood without snobbery,” and “all of the virtues and none of the vices of the average college fraternity” or sorority, according to the Excelsior pledge, but they were the site of some of the first acting performances on campus, though not under that moniker. A few of their events included a wide range of speeches, musical selections, tableaux, debates, pantomimes, dramatic readings, other oral recitations, and even student-written dramas. In fact, the first known drama to be performed at Wheaton College was Transformation of the Slaveholder, written by two students and produced by the Beltonian and Aelioian societies in 1867, with three acts and nine characters. Shortly after, the first performance of a published drama was in 1876, a presentation of Country Cousin at another open meeting of the societies.

The societies were viewed as a crucial part of Wheaton students’ intellectual and social development, and they remained popular long after literary societies at most schools had died out. Eventually, though, literary societies at Wheaton began to phase out around 1945. By 1959, the last literary society on campus had disbanded, marking the end of a significant era. However, its completion paved the way for far greater dramatic opportunities at Wheaton College.

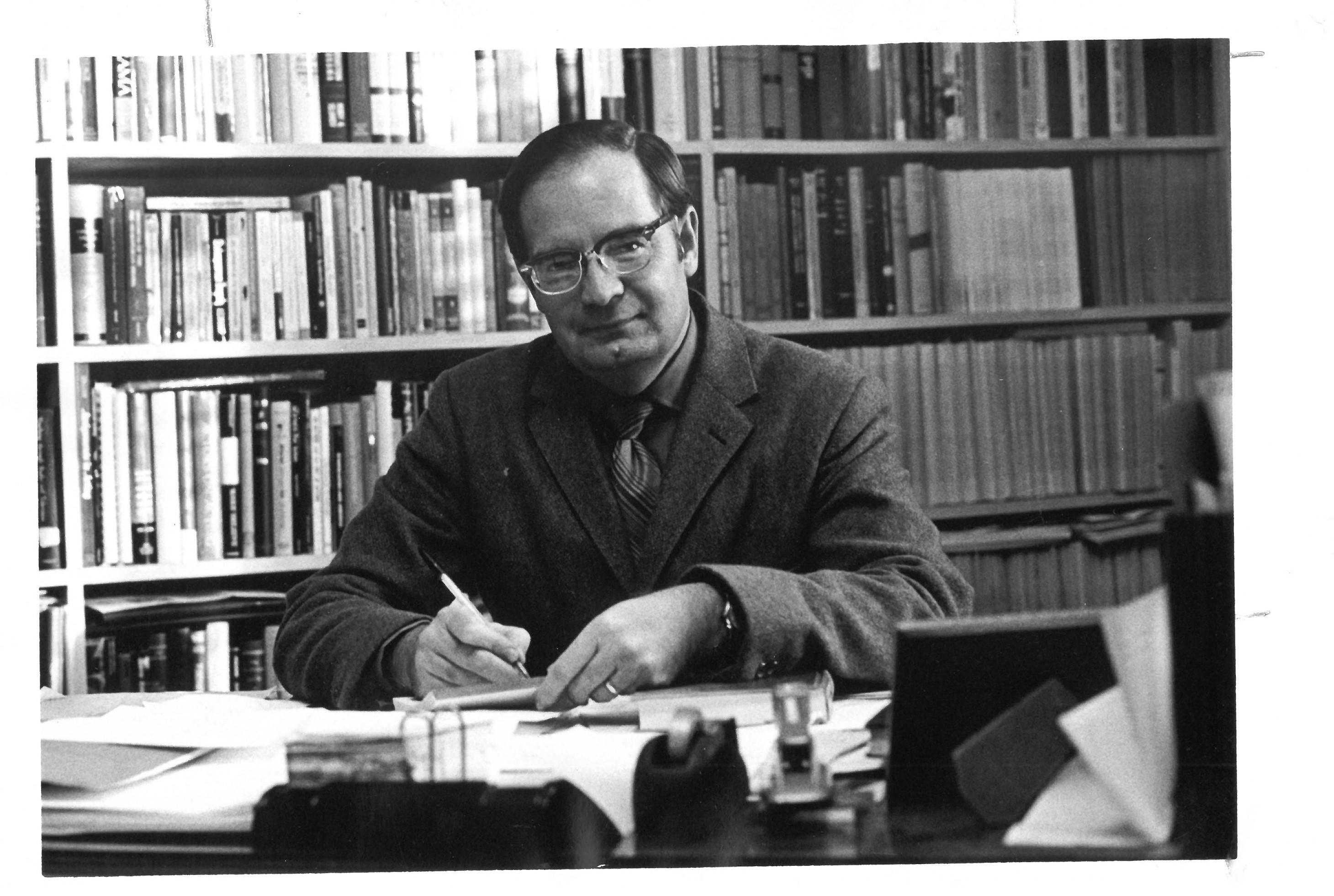

Enter one of the major heroes of our story: Dr. Edwin Hollatz M.A. ’55.

Dr. Edwin Hollatz at his desk.

Hollatz arrived at Wheaton as a graduate student in the fall of 1952, when he was assigned to the speech department. He was described to me by people who know him as someone who has always done it all, the consummate generalist, and his education was no exception. He balanced his time between Wheaton College and Northwestern University during the summers, earning two master’s degrees in radio production and Bible theology. When he achieved a graduate fellowship at Wheaton, he began teaching his own courses on radio writing and broadcasting. His work was so prolific that he was granted a faculty position at Wheaton in 1955.

Hollatz had two goals at Wheaton: get an official radio station and bring theater to the school. While simultaneously continuing his Ph.D. work at Northwestern, he began what would become an illustrious and lengthy career in the Department of Communication doing exactly that. Credited for turning WETN from a simple P.A. system to a fully functioning radio station, Hollatz would also go on to serve as director of broadcasting for 12 years and department chair for 20, in addition to his service as the debate coach over the course of several decades.

Hollatz is also essentially responsible for fully introducing theater at Wheaton. He taught the first official theater class, Introduction to the Dramatic Arts, and began equipping students with the knowledge of theater history, stage design, and directing. This culminated in Hollatz directing the first officially sanctioned play at Wheaton College, a production of Macbeth in 1966.

Larry King ’66, who played Banquo in this production, still remembers the excitement of this performance after the longstanding taboo. He described with perfect detail the set, including a tall box lit dramatically from within to make it seem as though Banquo’s ghost appeared out of nowhere, as well as the sleeves of Lady Macbeth’s gown that turned blood-red in the lights when she lifted her arms, so that her guilt after the assassination of Duncan was on display. He also remembers fondly one of Banquo’s most memorable lines, “That I myself should be the root and father of many kings,” since he is still married to his college girlfriend Karen Kany King ’68, who was in the audience at that very show. “Well, the witches’ prophecy was fulfilled, and we are heads of the family of many Kings,” Larry King joked.

Hollatz left a lasting impact on all the students and colleagues who knew him. Everyone still recalls his deep, resonant voice, his words intentional and articulate. This is the voice, Wheaton College Graduate School Chaplain Dr. Greg Anderson ’77 recalled, that once delivered an unbelievable reading of Scripture in St. Paul’s cathedral in London, a space where it is usually so difficult to be heard that members of the clergy came up and thanked him afterward for his oration. Hollatz was a communicator, believing steadfastly in “the Word made flesh,” and the established theater at Wheaton would not exist today without that iconic voice having spoken it into being.

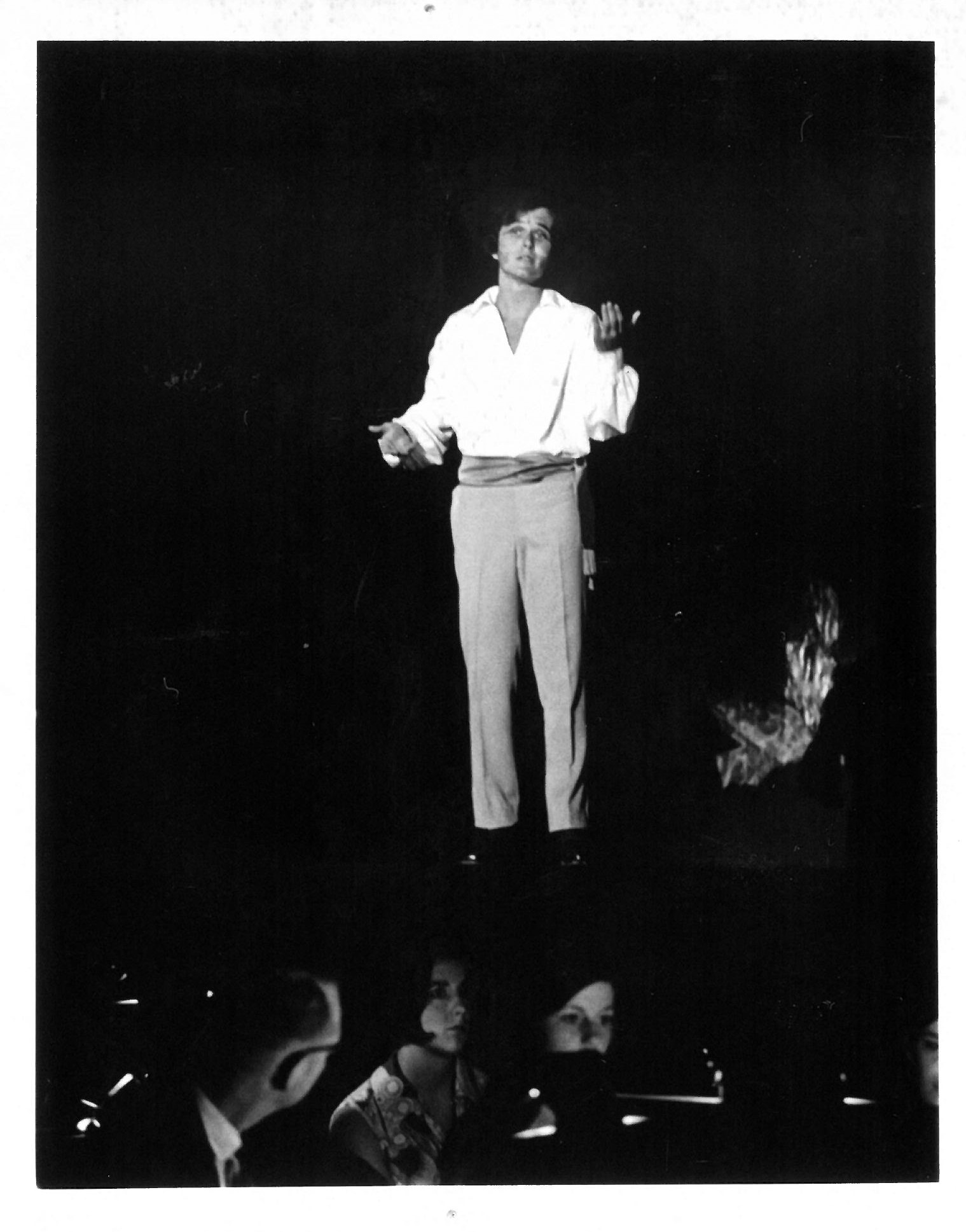

Mike Stauffer performs in a production of “On A Clear Day.”

1972

As we discovered in the main installment of this storied history, Michael Stauffer ’70 is one of the main pillars of Arena Theater, having served there as a professor, director, and stage designer for over 40 years. However, before his distinguished career as a faculty member, Stauffer was an undergraduate student at Wheaton in the 1960s. Shaped by a backdrop of thick social and political intrigue, including the Vietnam War, the draft, the 1968 Democratic Convention, and much more, Stauffer was involved in underground student-run productions in the basement of Plumb Studio, a large Victorian house where the Department of Communication resided at the time. In the late 60s, theater at Wheaton was beginning to expand dramatically, introducing new characters such as Eleanor Paulson ’47, a beloved speech teacher with a particularly compelling oral interpretation class, and Barbara Nickolich ’59, an accomplished professor with a Ph.D. in theater who served alongside Hollatz as a director at Wheaton for two years.

Despite these accomplishments, the theater very nearly fell apart at the end of the decade due to instability among leadership. After Nickolich left the college a few years later (after being elected Teacher of the Year by the student body), Ken Blackwell was hired as another director. He successfully produced several more plays before he also left the school. Just when drama at the college was on the verge of collapse, at the beginning of the 1970s, Hollatz made a move that would become Arena’s saving grace: He hired Jim Young. And in the fall of 1973, Young began the core theater company titled Workout, and we have reached the beginning of our original story.

Every good story has a beginning. Arena Theater’s origin story is just as fraught with challenges, love, scandal, and providence as the rest of its history, and perhaps I am not alone in finding comfort in that. From the start, the theater has been the unlikeliest of places, filled with the most unlikely people, and overcoming insurmountable odds in the most unlikely way.

It is never possible to tell the story fully, but as I studied the theater’s roots and watched how the providence of God has carried it through the decades, one thing is clear. From the very, very beginning, champions have fought at Wheaton College for the right of stories to be told.

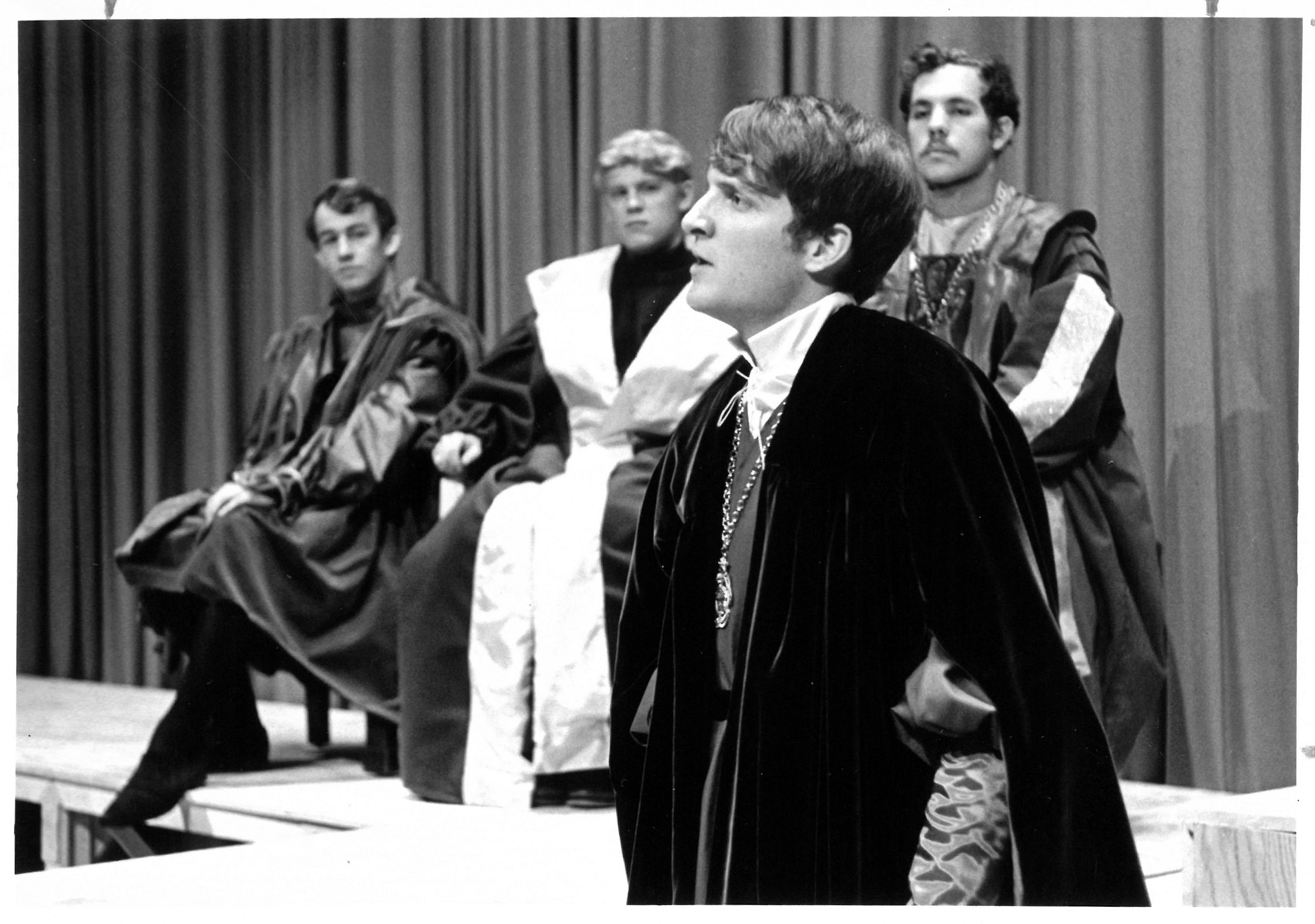

Students perform “A Man for All Seasons.”

1968