50 Years of Engineering at Wheaton College

Words: Melissa Schill Penney ’22

Photos: Diana Rowan

In 1972, Wheaton College welcomed the first cohort of its engineering program. Built on a 3-2 model—three years spent on Wheaton’s campus, and the final two spent at an ABET-accredited engineering program—the program opened the door for students to receive a Christian liberal arts education while also gaining necessary technical skills for their field. Fifty years later, the program has doubled in enrollment size and continues to offer increasing opportunities for its students and alumni.

Hands-on learning is key to the Wheaton engineering program model.

The Beginning

John Eisenbraun ’77 was one of two in the engineering program’s first graduating class. Although he was a guinea pig of the program, the decision to major in engineering at Wheaton was a no-brainer.

“I really like the choices I made, as far as pursuing liberal arts and engineering,” Eisenbraun said. “That’s something that has been somewhat unique about my education, and I wouldn’t trade it for a lot. It’s been very worthwhile for me.”

Eisenbraun completed his final two years of his engineering degree at the University of Michigan, then went on to become a software engineer, a profession that he has remained in for nearly 50 years now. He was just the beginning of a long line of Wheaton engineering graduates who went on to have successful careers and lives that made a positive impact on their communities.

Engineers, Missionaries, etc.

Students often end up pursuing engineering because they have been told they excel at math or science, or because they enjoy tinkering. Others come because they want to make an impact. Whether or not they stick with the profession, the skills and experiences gained at Wheaton set them up for success in nearly any field.

Three years studying at Wheaton College earn graduates of the program a bachelor’s degree in liberal arts engineering, while the two years spent at an ABET-accredited school earn the student a B.S. in whichever engineering field they pursue. While at Wheaton, engineering students work with an adjusted Christ at the Core curriculum to fit their studies into three years. This model ensures that students are not pigeonholed into one profession. Whether they go on to enjoy a long career in engineering or choose an alternate route, the liberal arts education they receive during college is designed to set them up for success.

Travis Klingforth ’99 attended Wheaton knowing he eventually wanted to pursue international ministry. While at Wheaton, Klingforth participated in the Human Needs and Global Resources (HNGR) program, for which he spent a semester in Tanzania, working with World Vision and the Tanzanian government to build water catchments for livestock herders. It was a hugely impactful experience for him as he volunteered alongside other committed followers of Jesus, got a glimpse of how small changes turn into big impacts, and learned how to adopt a posture of learning.

After graduation, Klingforth spent three years in the U.S. as a civil engineer, but his time in Tanzania set a lasting precedent for his career trajectory. He soon partnered with the Navigators, an international Christian ministry that emphasizes spiritual discipleship, and relocated to Kenya.

“Moving to Kenya, we imagined that some of my actual engineering skills and experience would be directly applicable,” Klingforth said. “But as you may know from community development practice and theory, you move at the pace of the community in the direction they want to go. Engineering was never a particular felt need for our community, so we went into other areas of health and education.”

Although his career and vocation may have taken a turn away from engineering, Wheaton provided Klingforth with the foundational skills he needed for his career. “As I look back at my experience with the Navigators, the varied skills that came from a broad liberal arts education were the most useful on a day-to-day basis,” Klingforth said. “I could plan and strategize and have clear communication with ministry colleagues and supporters and students that I was walking alongside.”

Even alumni who took a traditional engineering path after graduation appreciate the ways in which their liberal arts education prepared them for life both in and out of the workplace.

Jeff Oslund ’87 is one such example. As a high school student, he was looking for a Christian school that would provide academic rigor, which landed him at Wheaton. Once on campus, he realized that he enjoyed not only the College’s academics but also the many opportunities to be involved in ministry. He plugged into National Cities Ministries and the Christian Service Council, tutored at a local church, and participated in several short-term mission trips.

After graduation, Oslund began working for Motorola, and he’s been there ever since. As he took on different roles, from project management to people management, Oslund began to see the benefits of his time at Wheaton play out. ““So much of what I learned about the Bible and critical thinking and working with people at Wheaton has continued to be important in my career,” he said.

His Wheaton experiences have come in handy outside of work, too. Oslund is deeply rooted in his church community, where he leads ministries for middle and high school students. “My work is a tool, and I’ve enjoyed it and strive to do my best work, but it’s never been the most important thing in my life,” he said. “I push to have a balance and time to be involved in church.”

Engineering majors prepare for a class presentation.

Ann Lin ’19 is another engineering graduate whose path took a number of unexpected turns. She initially came to Wheaton with a curiosity for architecture but studied architectural engineering to see where it might lead. Lin was the only graduating female in her engineering cohort, and she often struggled to feel like she belonged. The scarcity of women in engineering is a theme across universities: In the United States, only 21% of engineering majors are women, according to research conducted by the American Association of University Women (AAUW) on the STEM gap. Amid this reality, Lin admitted her time at both Wheaton and the Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT) were difficult years for her personally. But after graduation, Lin landed a job she loved in healthcare mechanical engineering. “It was a total God thing,” she said. “I took a 180-degree turn. Engineering really opened up a lot of different hobbies for me.”

Currently, in addition to her full-time work as a mechanical engineer, Lin is an aspiring jazz and gospel pianist. Her advice to students is to “look for the group of people that really want to learn, that are really passionate in their studies or hobbies—people that are passionate about what they do. It really makes a difference in how you operate.”

Small School, Big Impact

Although Wheaton’s student body may be small compared to public institutions, the smaller faculty-to-student ratio only serves to amplify each program’s impact on students’ lives and careers. Committed faculty and staff, like Jeff Yoder, are part of making that positive impact happen.

Yoder spent a large part of his career in southern Africa and Southeast Asia, working primarily in water engineering, a subset of civil engineering. His passion for working with people to ensure they were connected with needed resources eventually led him to serve as the engineering program coordinator, and now the engineering program director, at Wheaton College.

Yoder has kept things running smoothly within the engineering program since 2017. Alongside administrative and advisory tasks, Yoder also teaches a handful of classes. His professional experiences inform his role as a career coach for students and have given him especially pertinent insight for students who want to use their engineering skills in an international or ministry-focused field.

“I really love being able to take what I have done and bring it back to the classroom,” Yoder said. “I think it’s meaningful for the students, and it brings me joy.”

One of Yoder’s primary responsibilities is facilitating transfers from Wheaton to ABET-accredited schools in the 3-2 program. “We do a lot of work to make sure the transfers go well, and by and large they do. Wheaton is well-respected, and we have students all over the country,” Yoder said. “When they go to their new schools, students report that they were well-prepared if not steps ahead.”

With the addition of the four-year model, Yoder’s responsibilities have shifted toward ensuring the success of the new program.

Running tests in the engineering laboratory on campus with Dr. Sean LaShell.

Jaclyn Baker Button ’12 was drawn to Wheaton specifically because of its co-terminal program with IIT. She appreciated the flexibility of being able to live and work on Wheaton’s campus, while simultaneously taking classes at IIT. Between her involvement in Jukebox Theater, intramural sports, pep band, and her Spanish minor, Wheaton was home, and she was able to enjoy it all the way through her fifth year.

Despite being well-prepared academically, the transition from Wheaton to a larger, secular institution can sometimes be a culture shock for students. Going from Wheaton’s small class sizes and easy access to professors to large classrooms taught by TAs can be a big shift.

“It’s interesting talking to students in their final two years of the 3-2 program,” Yoder said. “They almost always come back with an immense appreciation for Wheaton. At Wheaton, the classes are small and the students are in the lab from the beginning of their freshman year. The professors are really focused on teaching and caring for the students, and that makes all the difference in the world. You don’t get that everywhere.”

Becca Geiger Adamovicz ’20 experienced just that. When she transitioned to her final two years at IIT, the large class sizes and relative inaccessibility to professors were jarring for Adamovicz. “Professors had bigger priorities than teaching,” she explained. “It really put things into perspective, and grew my appreciation for Wheaton professors.”

Adamovicz was especially grateful for the work of Dr. David Hsu, who served as an assistant and associate professor of engineering at Wheaton from 2016 to 2023. Hsu began his career in mechanical engineering, then dabbled in biomedical engineering before deciding to pursue teaching. After graduating with his Ph.D., the engineering faculty position opened up at Wheaton. Hsu had never attended or worked at a Christian institution before and was impressed with the commitment and excitement that the students exuded.

As Wheaton’s first full-time engineering faculty member, Hsu had the opportunity to flesh out the bare-bones curriculum. “We got to do things in a completely new way,” he said. “There was no precedent or traditional style, so we decided to go with a project-based teaching method.” Hsu’s previous industry knowledge informed his decisions: “Because I had come from the industry and had those experiences, I realized what the industry is looking for. It’s about having graduates who want to work with people, are willing to collaborate and communicate well, and less about equations and drawing diagrams. Fortunately, that was well received by students. We got to teach the textbook problems alongside long-term multifaceted projects.”

Dr. David Hsu (right) with students in one of the engineering labs.

The project-based curriculum means that students regularly have the opportunity to be in the lab, ideating, designing, and building tools. For example, one group of engineering students knew a fellow Wheaton student who was born with a hand injury. Although he had always wanted to climb a rock wall, his disability was prohibitive. The engineering majors teamed up to create a functioning “hand” that the student could slip on and use to climb the rock wall.

“One of the things the program challenges its students to do is put themselves in the shoes of their client as much as possible,” Hsu said. “For this project, they ended up duct-taping their fingers together so they didn’t have finger mobility, to simulate the same lack of mobility as their client. We tried to approach projects from an empathetic perspective, which I think is probably the most important part of design.”

Hsu also introduced the angle of justice into the curriculum. Although engineers work under a code of ethics, time and time again designs and decisions pass through the ethics review yet still cause negative outcomes for looked-over individuals and communities.

“For engineering students at Wheaton who are Christians trying to impact the world in systematic ways, if they’re not aware of these justice dimensions on top of the ethics dimensions, they could cause harm,” Hsu said. “At the same time, if they are aware of these justice issues but are willing to compromise on their ethics, that is also a negative. You need both: ethics and justice.”

The Future

Fifty years after the launch of the 3-2 engineering degree, Wheaton introduced a four-year general engineering major for its undergraduates. The four-year structure allows students to remain on Wheaton’s campus for the entirety of their degree, and reduce tuition costs with one less year of classes.

This also opens more doors for engineering majors to connect with their peers across campus. They can spend more time and space completing curriculum requirements and taking full advantage of Wheaton’s liberal arts offerings, including general elective classes that match the student’s personal interests and other extracurricular groups.

Professor of Physics Dr. Darren Craig also sees the four-year degree as an opportunity to collaborate with other academic programs on campus, such as HNGR, the Humanitarian Disaster Institute, the Center for Faith and Innovation, and even the Department of Art.

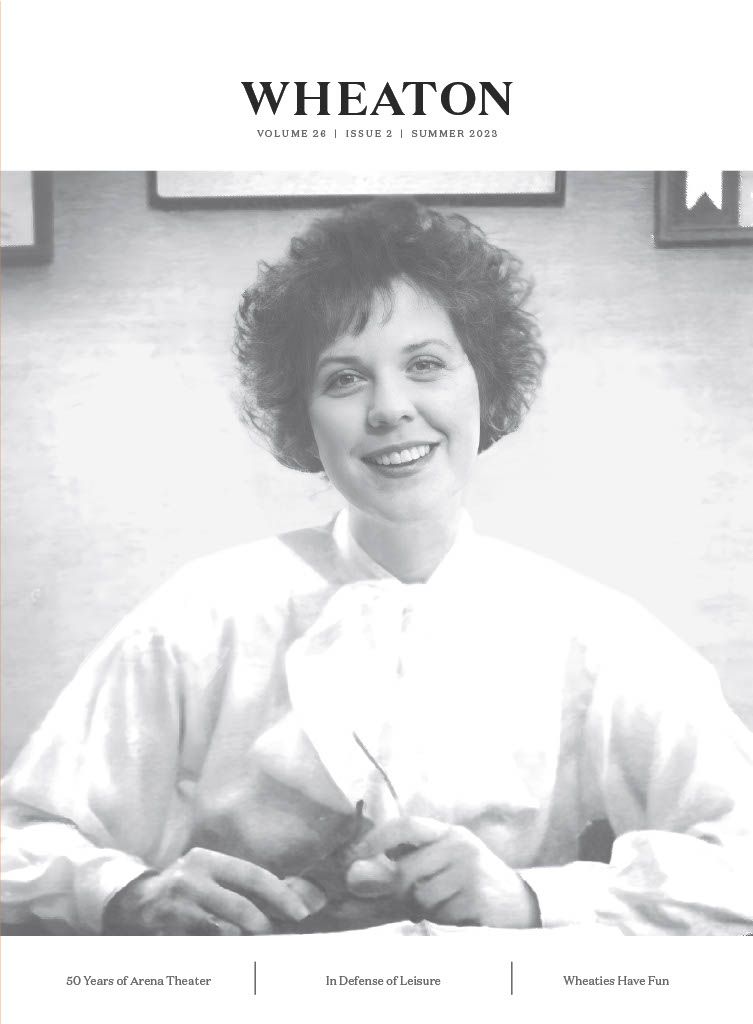

Dr. Kelly Vazquez

“To the extent that we can, we want to teach engineering as a liberal art,” Craig said. “That runs very crosswise in many peoples’ minds because it seems like engineering training is professional training while liberal arts training is not. However, there are ways of teaching engineering where you emphasize developing the whole person—from critical thinking skills to liberating a person to think beyond traditional boxes. A lot of those skills benefit engineers. We are keeping the spirit of the Wheaton education alive in the engineering program.”

With the growth of the engineering program also comes the expansion of resources. Dr. Kelly Vazquez joined the program as a new assistant professor of engineering, and the construction of an additional lab is currently in the planning phases.

Yoder acknowledged that Wheaton’s engineering facilities are small in comparison to major engineering universities. “But we want to compete in a different way, and that’s the quality of engineers in terms of their ability to grasp situations, adapt to them quickly, step into almost any environment, and in a short time become a leader.”

To learn more about engineering at Wheaton, visit wheaton.edu/engineering.