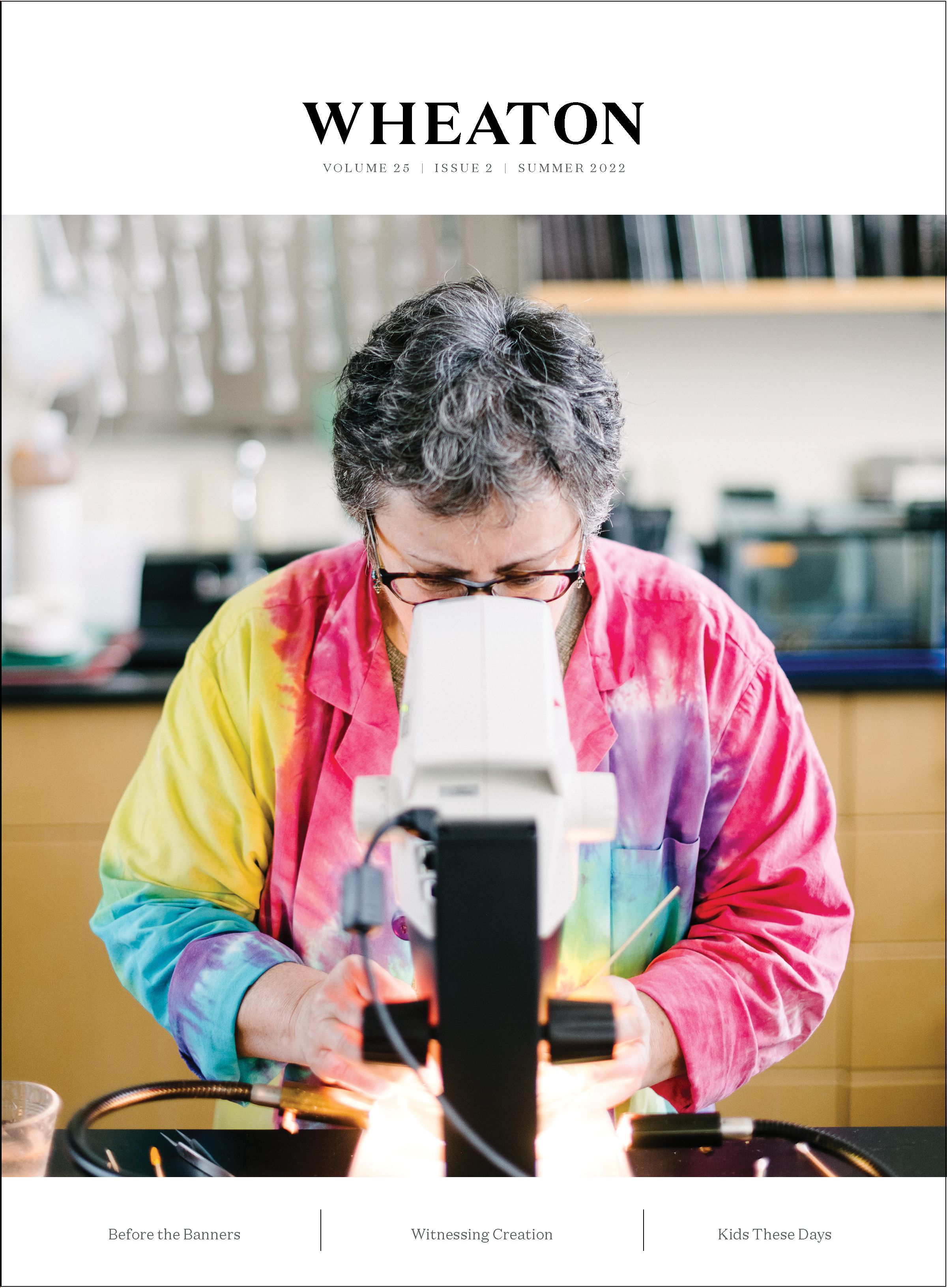

In Pursuit of Enduring Truth

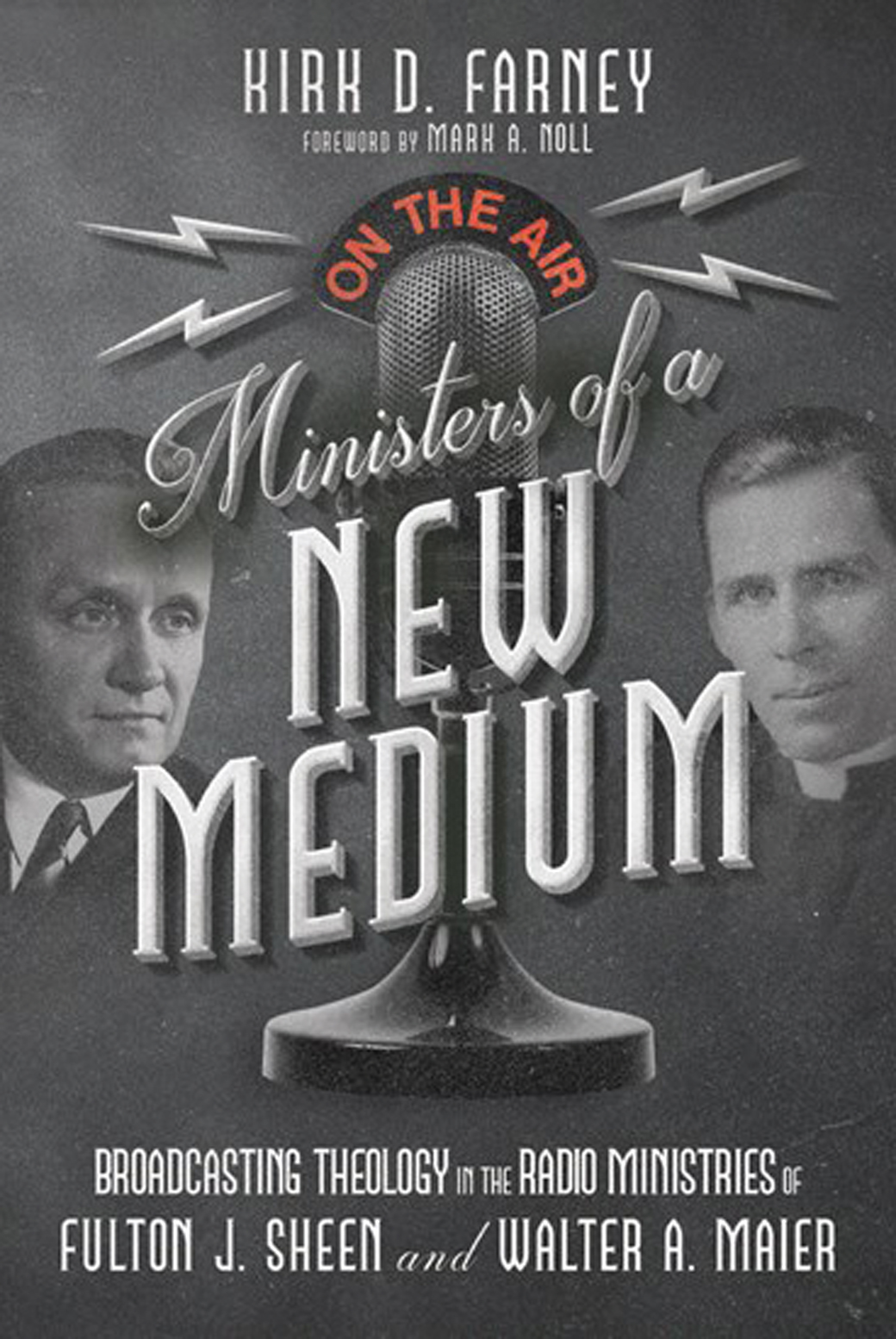

An Extended Q&A with Dr. Kirk Farney about his New Book on the Radio Ministries of Fulton J. Sheen and Walter A. Maier

Words: Melissa Schill ’22 and Eliana Chow ’21

Photos: Diana Sokolov Rowan

On June 21, Vice President for Advancement, Vocation, and Alumni Engagement Dr. Kirk Farney M.A. ’98 will release a new book, Ministers of a New Medium: Broadcasting Theology in the Radio Ministries of Fulton J. Sheen and Walter A. Maier (IVP Academic, 2022). Wheaton magazine sat down with Dr. Farney to discuss key themes from the book, which delves into the social, political, technological, and religious environments that left tens of millions of listeners hungry for theological truth.

The following transcript has been edited for brevity and clarity.

What initially inspired you to start working on Ministers of A New Medium?

In 2008, I was wrapping up my 26-year international banking career in the middle of a global financial crisis. As somebody who had a background in theology in addition to economics and the financial sphere, I decided to pursue a Ph.D. at the University of Notre Dame and explore how I could bring those two fields together. I started asking questions like: What were preachers preaching during the Great Depression and the years that followed? Did they preach the social gospel? Did they preach that people needed to be more charitable and hospitable? Did they suggest the reason all these bad things were the direct result of everyone’s sinful nature? I brought these topics to Mark Noll, then a professor of history at Notre Dame, and he affirmed that it was worth pursuing. Everything evolved from there.

Could you take us behind the scenes of your early research process?

I was already somewhat familiar with Walter Maier’s radio program The Lutheran Hour, so I started reading some of the published sermons from his broadcasts. As I engaged with those texts, I began finding noteworthy parallels between his words and those of Fulton Sheen, who appeared on the NBC radio series the Catholic Hour. I then spent an entire year reading almost every sermon they both preached over the course of their 20-plus year radio careers. I cataloged common themes and was amazed to discover that a Lutheran and a Catholic were saying so many similar things over national radio airwaves.

I found parallels in their life stories, as well. Both Maier and Sheen came from denominations that in the 1930s were viewed as peripheral in the North American Christian scene. Catholics, though significant in number, were often considered immigrant outsiders. Lutherans were known for being largely of German and Scandinavian descent and rather sectarian. Yet almost 20 million people tuned in to listen to these guys every week.

From social, cultural, and ecclesiastical points of view, it was fascinating to me that the staunchly orthodox sermons these clerics delivered had such a large following during a time of acute distress—the Great Depression, World War II, and the beginning of the Cold War. With the confluence of national and international calamity, the emergence of radio technology, and an evolving pastoral role in society, these events helped mark the genesis of mass culture and a shift in American religious life. I wanted to explore that intersection more closely.

What were some of the key factors that contributed to Maier’s and Sheen’s success during such stressful times?

During its “Golden Era,” radio served as a source of information and entertainment. The latter category included music, drama, and comedies. Comedies were a particularly welcome distraction from the woes of the day. They were well-written, topical, and skilfully performed. I can’t listen to a recording of The Fred Allen Show without laughing aloud. In contrast, Maier and Sheen went on-air not to entertain, but to tell people about sin, repentance, and salvation through Christ—and listeners responded in droves. That’s a remarkable thing. They were unlike preachers who developed their own following because of their antics. These guys certainly had celebrity, but it was the theological substance that drew their audiences.

Many of their messages centered around capital “T” Truths, such as the atonement. While editing my manuscript, one of my readers suggested that I cut back on the theology sections of the book, in part because I gave several examples of how Maier and Sheen talked about atonement. I was told, “You could probably get by with just one. Let’s face it: The atonement is kind of boring.” I went home and started cutting some of my material, but then realized, “That’s the point. The atonement seems boring and yet 20 million people tuned in every week to hear about it. That’s the story.” What we might consider esoteric or overly repetitive, people wanted to hear on a regular basis.

To that end, Maier and Sheen also embraced technology. Although there were some people who felt like radio was a passing fad, these radio preachers took a popular entertainment medium and leveraged it to convey eternal truths. They were certainly not the only ones to do so, but they did it very early on and they did it effectively. They were disciplined in what they spoke about. They spoke about theologically weighty concepts. They talked about social issues and current events, while purposely staying away from politics. They didn’t endorse candidates, they didn’t talk about parties, and they didn’t talk about public policy for the most part. Rather, they spoke of scriptural truths and their temporal and eternal ramifications.

How did the radio format shape the way people received Maier and Sheen’s message?

At a time when religion seemed to be declining, millions of people were hearing the gospel through a new avenue. They heard this pastor—who they felt was addressing them personally—and they projected considerable authority on him because he was a familiar voice on national radio.

Listeners also perceived radio as an intimate form of technology, as they chose which voices to allow into their parlors through the twist of a dial. Although we tend to think of radio as a form of mass media, earlier listeners thought of it as very individualistic. “I’m the one who has the choice here. I can decide whether to listen to Jack Benny or Bob Hope or Kate Smith and I have ultimate control.” There was a perceived power they held as the consumer.

By writing letters to the hosts, listeners also had the chance to exercise their agency and engage with the ideas presented on air. At one point, Maier had 100 full-time secretaries just to answer mail. Ultimately, the radio allowed for a perceived intimacy combined with authority.

As you anticipate the upcoming book launch, what key takeaways have you gleaned from the research and writing experience?

Embracing technology, whatever it is, can be the avenue by which old truths can be conveyed to new audiences. Does that mean everyone needs to follow a certain pattern? No. There are some people who are very good podcast hosts but I wouldn’t watch them for five minutes on TV. There are others who write really great online articles who I wouldn’t care to listen to on a podcast. Not everyone is equipped to take the same path, but developing an openness to sharing enduring truths to new audiences through new avenues is always a worthwhile pursuit.

One of my professors once made the point that when you’re cooped up for so many years writing about a couple of people, you start to experience Stockholm syndrome. I love these guys and wish I could sit down and have dinner with them. I find these two clerics to be incredibly inspiring in part because I love words and they were masters at using words, but also because they were skilled orators. They understood that if you delivered a message consistently and well—even if it’s a challenging message—people will listen.

Faculty Receive Promotions and Tenure

The following faculty promotion, tenure, and emeritus status actions were approved by the Board of Trustees in February and are effective July 1, 2022.

EMERITUS

Dr. Mary Hopper ’73

Professor of Music Emerita (43 years of service, 1979–2022)

After attending Wheaton as a student, Dr. Mary Hopper returned in 1979 and has served for 43 years as a music pro- fessor and performance studies director. To the campus community and Wheaton College Conservatory patrons, she is most recognizable onstage, where she conducted the Men’s Glee Club and the Women’s Chorale.

Mr. Michael Stauffer ’70

Professor of Communication/Theater Emeritus (43 years of service, 1979–2022)

Mr. Michael Stauffer joined the Wheaton faculty in 1979 and served for 43 years as a communication professor. Stauffer attended Wheaton as an undergraduate, then pursued master’s degrees in directing and stage design. His directing and designing expertise found an outlet in Arena Theater, Wheaton’s theatrical community, where he has helped put on over 50 plays.

Dr. Laura A. Barwegen

Associate Professor of Christian Formation and Ministry Emerita (20 years of service, 2002–2022)

After a career as a middle school teacher, Dr. Laura Bar- wegen transitioned to teaching undergraduates, which she has done at Wheaton for 20 years. Her classes, many of which explore the intersection of neuroscience and faith, invite students to grow both intellectually and spiritually.

Dr. Douglas L. Penney ’77

Associate Professor of Classical Languages Emeritus (31 years of service, 1991–2022)

Dr. Douglas Penney first attended Wheaton as an under- graduate, then returned in 1991 to teach at his alma mater as a professor of classical languages. During his 31 years of teaching, he gained a reputation on campus for making Greek accessible and fun to learn.

TENURE

Dr. Thomas Martin, Professor of English

Dr. Jovanka Tepavčević, Associate Professor of Biology

PROMOTION FROM ASSISTANT PROFESSOR TO ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR

Mr. Andy Mangin ’99, Associate Professor of Theater and Communication

Dr. Esau McCaulley, Associate Professor of New Testament

Dr. Timothy Taylor, Associate Professor of Politics and International Relations

PROMOTION FROM ASSISTANT PROFESSOR TO ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR AND TENURE

Dr. Ryan Kemp, Associate Professor of Philosophy

Dr. Hanmee Kim, Associate Professor of History

Dr. John McConnell, Associate Professor of Psychology

Dr. Rebecca Sietman, Associate Professor of Communication

PROMOTION FROM ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR TO PROFESSOR

Dr. Andrew Abernethy, Professor of Old Testament

Dr. James Beitler ’02, M.A. ’04, Professor of English

Dr. Ward Davis, Professor of Psychology

Dr. David Lauber ’89, Professor of Theology

Dr. John Trotter, Professor of Music